Discoveries of Eilat Mazar: The Summit of the City of David

Jerusalem today is a large, bustling city covering nearly 125 square kilometers, with a sprawling metro area of over 650 square kilometers. More than 2 million people live in the Jerusalem metropolitan area.

Compared to modern Jerusalem, the Jerusalem of King David’s time was minuscule. Situated on a crescent-shaped mountain ridge, the “city of David” was only about 12 acres in size. Yet this tiny speck of land was the setting for some of history’s most epic events and personalities.

Naturally, Jerusalem’s long, rich history attracts the attention of historians. For archaeologists—historians who like to use spades as well as books—Jerusalem is the ultimate place to excavate. And some few have. Beginning in the mid-19th century, a handful of archaeologists have excavated various parts of the “original” hill of Jerusalem, most notably Sir Charles Warren, R. A. S. Macalister and Dame Kathleen Kenyon.

In the early 1980s, Prof. Yigal Shiloh undertook excavations at a site known as “Area G” at the summit of the City of David. On his staff was a young, energetic, recently graduated archaeologist. She was newly married and had just delivered her first child. Her name was Eilat Mazar.

Eilat might have only just graduated, but she wasn’t inexperienced. As the granddaughter of Prof. Benjamin Mazar, one of Israel’s top historians and archaeologists, Eilat had spent her childhood visiting and working on archaeological sites all across Israel. Within two weeks of starting work on Professor Shiloh’s City of David dig, Eilat had moved from assistant area supervisor to area supervisor. Between her degree, her experience and legacy, and her unmatched enthusiasm and work ethic, Eilat was destined for greatness.

When Yigal Shiloh died in 1987, it was Eilat who, in a sense, picked up his mantle in the City of David.

Discovery One: King David’s Palace

When David became Israel’s king, Jerusalem (called “Jebus”) was inhabited by the Jebusites. As king, one of David’s top priorities was capturing Jerusalem. David understood Jerusalem’s connection to Abraham, and he knew Jerusalem would be Israel’s capital city.

2 Samuel 5 describes how David and his army conquered Jebus by penetrating the fortress through a series of underground water tunnels. After taking the city, King David (with the help of King Hiram of Tyre) built his palace and then “waxed greater and greater” (verse 10). Given the small size of Jebus, archaeologists have wondered how there was room enough for a royal palace. One theory was that King David demolished the existing Jebusite structures in order to make room for his new palace.

In 1996, when Eilat Mazar began thinking about and researching this question, she did something entirely logical but all too rare in the field of archaeology. She researched the Bible’s answer to these questions. “Pore over [the Bible] again and again, for it contains within it descriptions of genuine historical reality,” her grandfather had taught her. So this is what Mazar did.

When she studied 2 Samuel 5, one particular verse leapt into focus. “And when the Philistines heard that David was anointed king over Israel, all the Philistines went up to seek David; and David heard of it, and went down to the hold” (verse 17). Mazar noted that the word “hold” was the same word for the Jebusite fortress itself—metsuda (mentioned in verse 7). She also noted the fact that when threatened by the Philistines, David went down and into the fortress from his dwelling place.

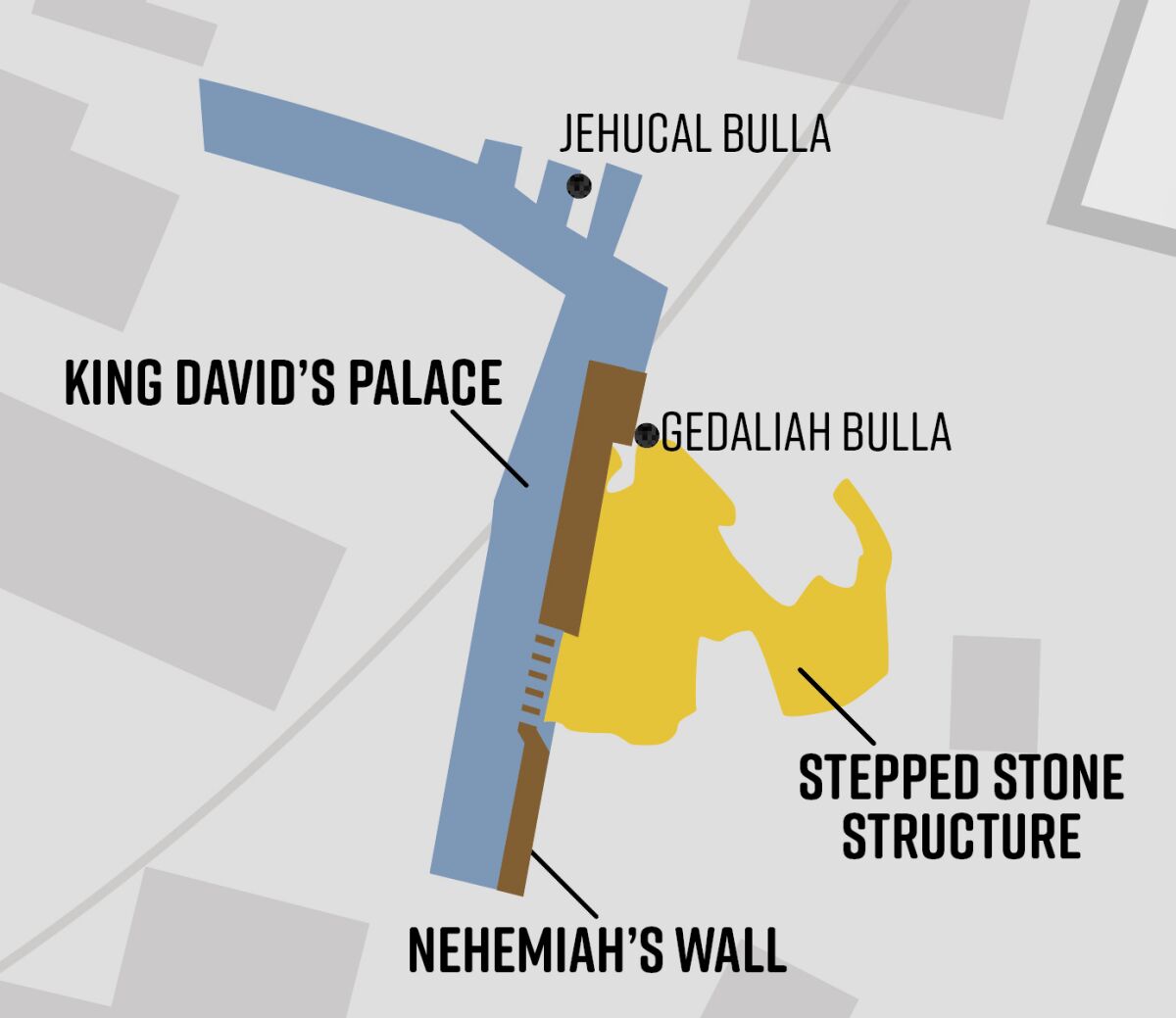

In order to do this, Mazar concluded, David’s palace must have been situated at the summit of the City of David, just outside the northern edge of the Jebusite city, in a location not yet within the fortress itself.

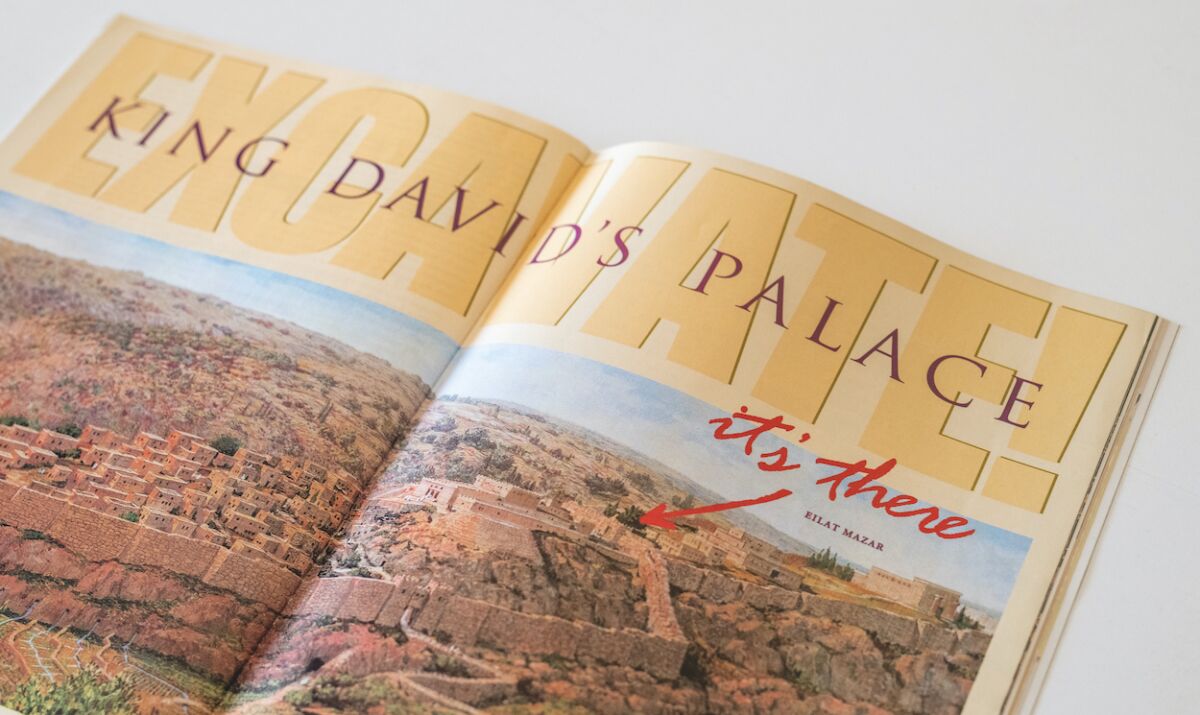

In 1997, after almost a year of researching this theory—and having just received her doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem—Dr. Mazar, with her grandfather’s encouragement and support, published her theory in Biblical Archaeology Review. Her article, titled “Excavate King David’s Palace!”, left no doubt about her intentions.

“A careful examination of the biblical text combined with sometimes unnoticed results of modern archaeological excavations in Jerusalem enable us, I believe, to locate the site of King David’s palace,” she wrote. “Even more exciting, it is in an area that is now available for excavation. If some regard as too speculative the hypothesis I shall put forth in this article, my reply is simply this: Let us put it to the test in the way archaeologists always try to test their theories—by excavation.”

The article was accompanied by a large photograph of the City of David, with a giant arrow pointing to the spot she believed King David’s palace could be found. “It’s there,” she boldly declared.

Mazar’s theory was met with some scholarly resistance, partly due to the fact that past excavations in the area had not unearthed any evidence to prove this theory. The skepticism over Mazar’s theory made it difficult to raise the funds necessary to dig. It wasn’t until 2005, nearly a decade after Mazar originally published her theory, that two brave American philanthropists stepped forward to back Mazar. In February, thanks to the support of Roger and Susan Hertog, Mazar was finally able to put her theory to the test—by excavation!

Within weeks, Mazar and her team discovered the foundations of a massive wall. Measuring 30 meters long and up to 3 meters wide in places, this was not a wall of any ordinary structure. Moreover, Dr. Mazar was able to date the giant edifice to the 11th–10th centuries b.c.e.—the same period as King David. The dig was off to a spectacular start, and the best was yet to come.

The following season (2006), Mazar discovered another even larger wall. In some places, this wall measured 6 meters wide. Just as significantly, this larger wall connected with the giant walls uncovered earlier, indicating that both were part of the same massive structure.

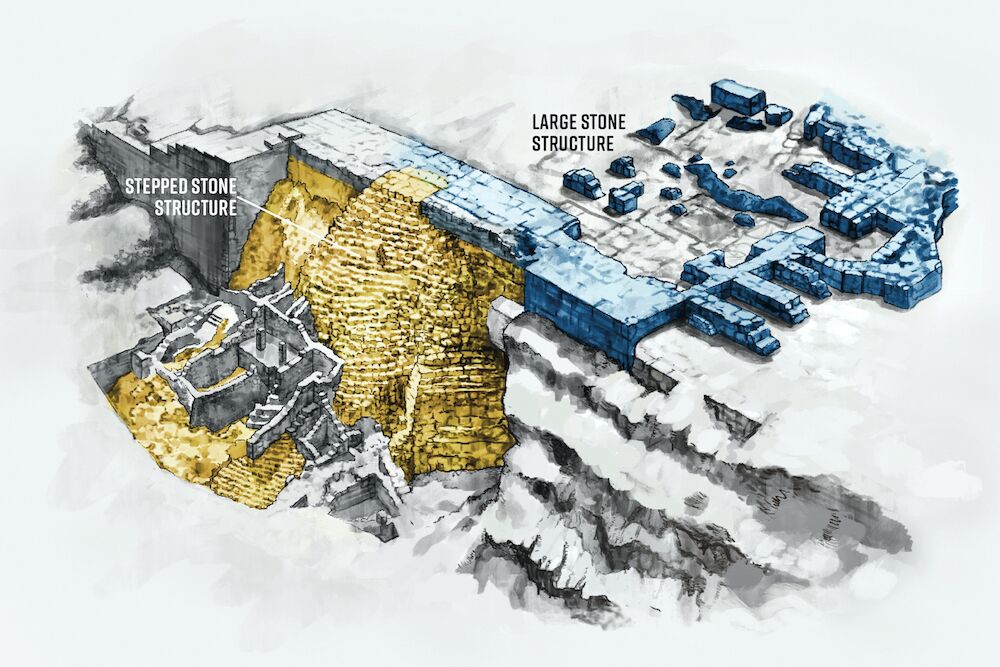

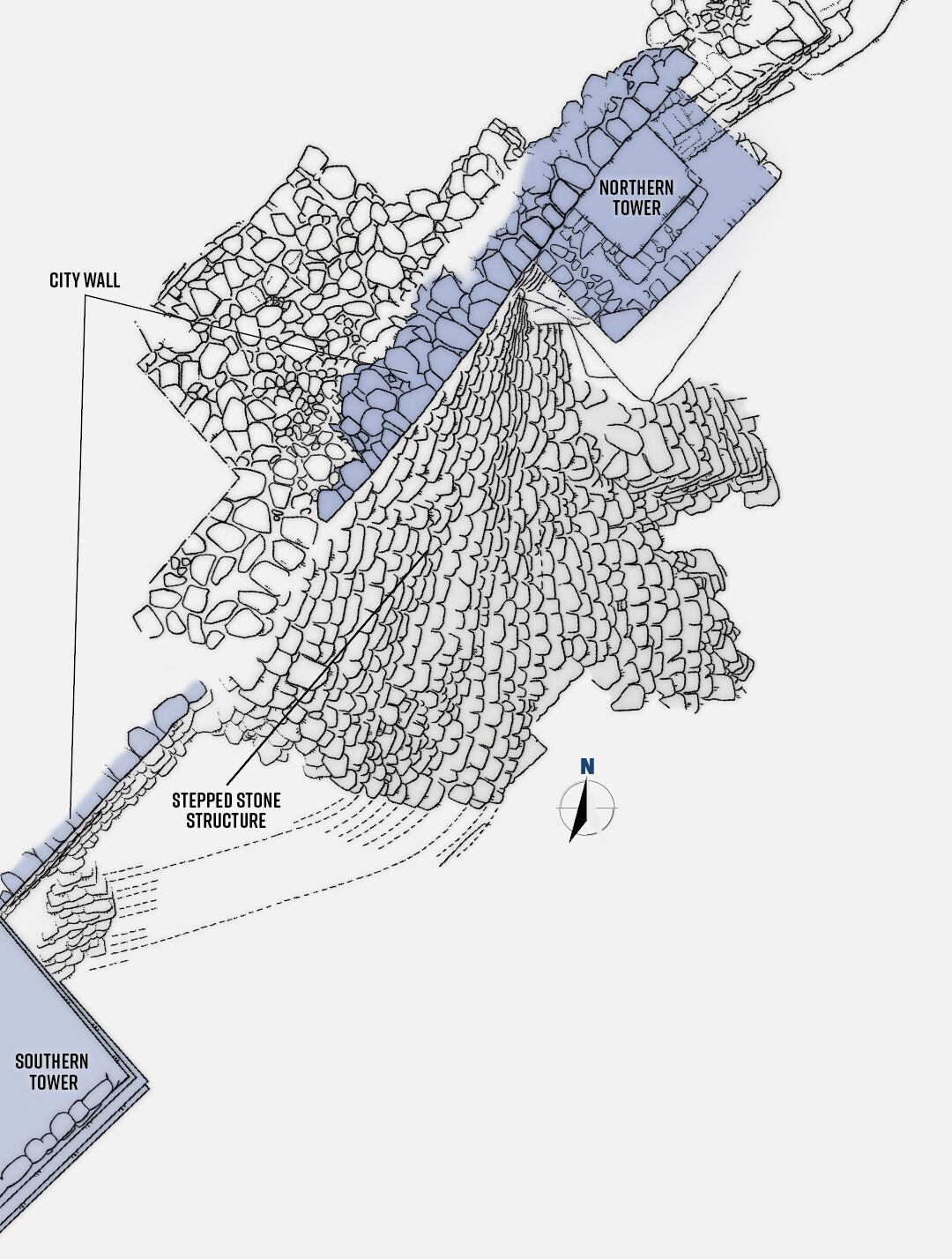

In 2007, during the third season, Mazar made another crucial discovery. She learned that the walls of the grand, palatial structure found in the previous excavations actually interlocked with the famous Stepped Stone Structure. Standing 20 meters tall and clearly visible from the Mount of Olives across the valley, the Stepped Stone Structure is the largest uncovered Iron Age structure in Israel. Prior to Mazar’s discovery, many archaeologists believed the Stepped Stone Structure was built during the Jebusite control of Jerusalem.

But the fact that the walls Mazar uncovered interlocked with the Stepped Stone Structure indicated that both the walls and the Stepped Stone Structure were part of the same massive Davidic-era building!

“The fact that the two structures were part of the same construction was an astonishing discovery for us,” Mazar said. “Laid before our very eyes was a structure massive in proportions and innovative in complexity. It bears witness to the impressive architectural skill and considerable investment of its builders, to the competency of a determined central ruling authority, and most notably to the audacity and vision of that authority.”

To go along with the massive walls, various pottery finds and the carbon samples all pointing to a large-scale construction dating to circa 1000 b.c.e., Mazar also found a number of smaller finds that demonstrated the royal nature of the structure. These included ornate ivory utensils, remains of exotic foods and seals of royal individuals—all finds that attest to a royal edifice.

In her reports on the palace excavations, Mazar also recalled the discovery of a royal Phoenician style pillar capital by Kathleen Kenyon at the base of the Stepped Stone Structure. A pillar capital is the decorative upper part of a column. Capitals are often adorned with intricate carvings. Dr. Mazar’s giant walls and associated finds reveal how it got there: This Phoenician-style pillar capital must have fallen down from King David’s palace (built with the assistance of the Phoenician King Hiram), which was situated directly atop the Stepped Stone Structure!

In a 2005 article for Aish.com, Rachel Ginsberg recognized the significance of Dr. Mazar’s palace-of-David discovery: “Dr. Eilat Mazar, world authority on Jerusalem’s past, has taken King David out of the pages of the Bible and put him back into living history. Mazar’s latest excavation in the City of David, in the southern shadow of the Temple Mount, has shaken up the archaeological world” (emphasis added).

Discoveries Two and Three: The Jehucal and Gedaliah Bullae

During the 2005 excavation season, Dr. Mazar’s area supervisor, Yoav Farhi, made a remarkable discovery. Working on the dig one day, he spotted a tiny bulla (clay seal impression) sitting in the crack of a wall, the sunlight glancing off its raised letters. Mazar took the bulla home to study it and later recalled a “special” family moment she experienced while deciphering it.

Using a lexicon that had been compiled by her second husband, himself an archaeologist who had died in 1997, Mazar found that the bulla read “Belonging to Jehucal, son of Shelemiah, son of Shovi.”

Mazar then opened her Bible encyclopedia, curious if the name appeared in the Bible. “When I opened the encyclopedia and saw the same name in the Bible as was on the bulla, I let out a shriek of surprise that rang out through the still house. Fortunately, the children slept soundly. I felt as though I had just ‘resurrected’ someone straight out of the Bible,” she wrote. She later brought together her children and showed them how she had used their father’s lexicon to compare and translate the Hebrew text.

Jeremiah 37:3 records that Judah’s King Zedekiah sent Prince Jehucal, son of Shelemiah to the Prophet Jeremiah to beseech him to pray for Judah. Jehucal is also one of the princes who conspired against Jeremiah in Jeremiah 38:1-6—here, he is referred to by the shortened form, “Jucal.”

But the Jehucal-bulla find wasn’t the end of this remarkable tale. Two years later, Mazar’s wet-sifting team discovered another bulla from a nearby area. This one was inscribed with the words, “Belonging to Gedaliah, son of Pashur.” Once again, Dr. Mazar searched the Bible, curious if this man was mentioned. Amazingly, she discovered that “Gedaliah, son of Pashur” is mentioned right alongside Jehucal in Jeremiah 38:1. He was another one of the princes who sought to kill Jeremiah the prophet!

The Jehucal and Gedaliah bullae are two of nearly 250 seals, bullae and bullae fragments discovered by Mazar in the City of David excavations. The sheer number of official and royal paraphernalia attests to this specific location being used as a royal administrative area right up until the destruction of Jerusalem around 586 b.c.e.

Moreover, Mazar’s finds fit with the discoveries made by Shiloh’s team in the 1970s and ’80s—notably a “House of Bullae.” In a single room uncovered alongside the Stepped Stone Structure, Shiloh uncovered 51 bullae, including another biblical individual: “Gemariah, son of Shaphan.” Who was Gemariah? He was a scribe in the court of King Jehoiakim, mentioned in Jeremiah 36:10. Refreshingly different from Jehucal and Gedaliah, Gemariah was one of the few people who supported the work of Jeremiah the prophet.

Discovery Four: Nehemiah’s Wall

During the Phase 2 excavation of the City of David in 2007, Dr. Mazar began a simple salvage excavation of a short and stout tower that was commonly assumed to be Hasmonean (second to first century b.c.e.). Because the tower could not continue to be repaired without risk of collapse, Mazar was required to thoroughly deconstruct it, carefully documenting the stones and their positions, so that a new foundation could be laid and the tower reconstructed.

The excavation led to a sensational discovery nobody expected.

Beneath the tower, excavators found the remains of two deliberately buried dogs, along with a wealth of Persian-period pottery and assorted finds. The two dogs, buried after dying of old age, also indicated the wall was built during the Persian period. In Persia, dogs held a special status; excavations elsewhere in Israel have uncovered similar large-scale dog burials dating to the Persian period.

Using pottery typology—which clearly pointed to the early part of the Persian period—as well as the dog burials, Mazar dated the construction of the wall to around 450 b.c.e.

As she always did, and just as her grandfather taught her, Mazar turned to the Bible to better understand this poorly constructed wall from the Persian period. This search led her to the book of Nehemiah. This book documents the history of a Jewish servant (Nehemiah) who worked in the royal court of the Persian king Artaxerxes but then returned to Jerusalem to help rebuild the city. These events occurred in the mid-fifth century b.c.e.

Upon returning to Jerusalem, Nehemiah (instated as governor) immediately conducted a reconnaissance of the city and determined that the city urgently needed its broken-down walls to be refortified. With a spade in one hand and a sword to fight off enemies in the other, Nehemiah and his supporters worked rapidly to build a wall around Jerusalem. Remarkably, and to the great surprise of their enemies, Nehemiah’s wall was “finished in the twenty and fifth day of the month Elul, in fifty and two days” (Nehemiah 6:15-16).

While building a wall in such a short space of time is impressive, it comes with a downside. The quality of construction suffers. The tower and short preserved section of wall was of a notably poorer, “rushed” quality and finish, as Mazar noted.

One final point: The section of wall Mazar excavated was situated atop the Stepped Stone Structure. Was this section of the wall the same section described in Nehemiah 3:15-16 and 12:37, a section of wall built by Shallun and Nehemiah, against “the stairs that go down from the city of David,” alongside the “house of David”?

Discovery Five: Joab’s Tunnel

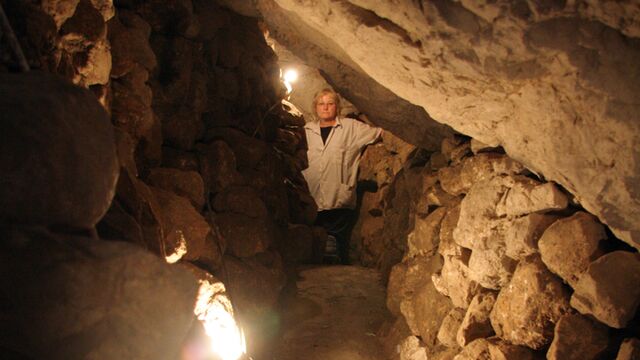

2008 was the last year Dr. Mazar would drive a shovel into the soil at the City of David. In this excavation, Mazar’s team discovered an ancient tunnel in the bedrock behind the Stepped Stone Structure. The tunnel was traceable to almost 50 meters long and barely wide enough for a man to squeeze through. Mazar believed the tunnel may have been used for channeling water, and was eventually integrated into the construction of the Stepped Stone Structure during the 10th century b.c.e., at the time of King David’s construction at the site.

Mazar wondered if the tunnel might be the one featured in 2 Samuel 5. “The tunnel’s characteristics, date and location testify with high probability that the water tunnel is the one called tsinnor in the story of King David’s conquest of Jerusalem,” said Mazar. The passage reads: “Now David said on that day, ‘Whoever climbs up by way of the water shaft [tsinnor] and defeats the Jebusites … he shall be chief and captain’” (2 Samuel 5:8; New King James Version). One of David’s mighty military men, Joab, did just that to infiltrate the city (1 Chronicles 11:6).

Mazar and her team discovered this tunnel near the end of the 2008 season. There wasn’t enough time to investigate further, which means the tunnel is not yet fully excavated. “We have a general knowledge of the tunnel,” she said, “but we are far from having a complete picture.” Let’s hope Mazar’s tunnel excavation can soon be completed and its no-doubt remarkable history be revealed!