The Antiquity of the Scriptures: The Prophets

The dating of the Bible is a controversial topic. Traditionalists say the Torah was written by Moses; the Psalms, mostly by David; Proverbs by Solomon; the prophets—by whichever name is carried in the title. Daniel? Sixth century b.c.e.

Revisionists, on the other hand, say the Torah was written after the Babylonian captivity—along with everything else, really. Daniel? Second century b.c.e. Books of individual names were most likely written by multiple ghostwriters.

This is a hot-button debate. Can we really know the answer? Just how ancient and authentic are the biblical writings? This article continues our three-part series, examining the textual content, linguistic style, archaeological evidence and contemporary works related to this question. The Tanakh, or Old Testament, is divided into three main sections: the Torah (Law), the Prophets, and the Writings. For this second installment, we’ll look at the Prophets, examining a sampling of the biblical books that fall into this category.

The Book of Isaiah

The book of Isaiah—traditionally dated to the eighth century b.c.e.—has faced a great deal of scrutiny. It is usually considered by revisionists to be the work of at least two authors (the second writing from chapter 40 onward), or perhaps even by as many as five different writers.

The central logic against the traditional dating for the book of Isaiah is that there is no way a prophet could tell the future. For example, Isaiah prophesies by name the future King Cyrus and the precise destruction of Babylon over 150 years in advance. Thus, the book must have been written at a later date. That supposition has caused some critics to identify changes in writing style throughout the book, which they say prove a later-written forgery. Could this be the case?

The truth is, these supposed changes in style cannot really be held up with any credibility. Isaiah 1:1 states that the prophet was writing and working during the reigns of five successive kings. He was prophesying over the course of about 60 years. Of course there would be a change in his writing style. Research has been done regarding changes in writing style. As a January 1971 Tomorrow’s World article stated:

The fact of the matter is that an accomplished author’s writing style should and will change through the years …. [L]iterary analysis has claimed that Paul only wrote five of his 14 epistles, that Ian Fleming didn’t write James Bond, and that the works of Graham Greene and G. K. Chesterton had “more than one author.”

It’s even been concluded, by such a standard, that James Joyce’s Ulysses was written by five different authors. Of course, this is ridiculous, but that is the conclusion we must draw if we are to hold these other authors to the same standard revisionists hold Isaiah.

Change in form can be either deliberate, or unintentional over several months or years—this is no gauge for the authorship of Isaiah. Any expert will tell you that to even begin to get a real sense of authorship based on writing style, you need a body of work far larger than Isaiah.

Ancient classical historians and early writers, back to about 200 b.c.e., gave Isaiah full attribution for the book—not for just half of it. It is interesting—and so typical—that more than 2,200 years on, we today fancy ourselves more knowledgeable than those who lived close to such an ancient time period.

In fact, much stylistic evidence can be given to show Isaiah wrote the entire book. An exhaustive comparative study of this can be found in Rachel Margalioth’s The Indivisible Isaiah. We won’t go into detail on the specifics of this here.

There is no question that Isaiah himself was an early prophet. Even those who do try to bring forward the date of the book only do so as far as the sixth to fifth century b.c.e. Isaiah’s writing is of an early Hebrew style, and he accurately describes the environment and politics of his time. These things have been verified through archaeology.

One of the major theories for Isaiah is that the latter half was written by a Babylonian captive around 540 b.c.e. Yet this is ridiculous when one considers the text within the latter half of Isaiah. Accurate descriptions are given of the land of Israel, including descriptions of numerous native trees—landscape that a captive in Babylon, by then at least 46 years into captivity, would not have been able to portray. Furthermore, the latter half of Isaiah describes the requirement for sacrifices at the temple. This, of course, would be redundant if it was admonition written in 540 b.c.e., after the destruction of the temple. Further, this text criticizes Canaanite idolatry, as opposed to Babylonian idolatry—a topic that by that time would have been rather redundant.

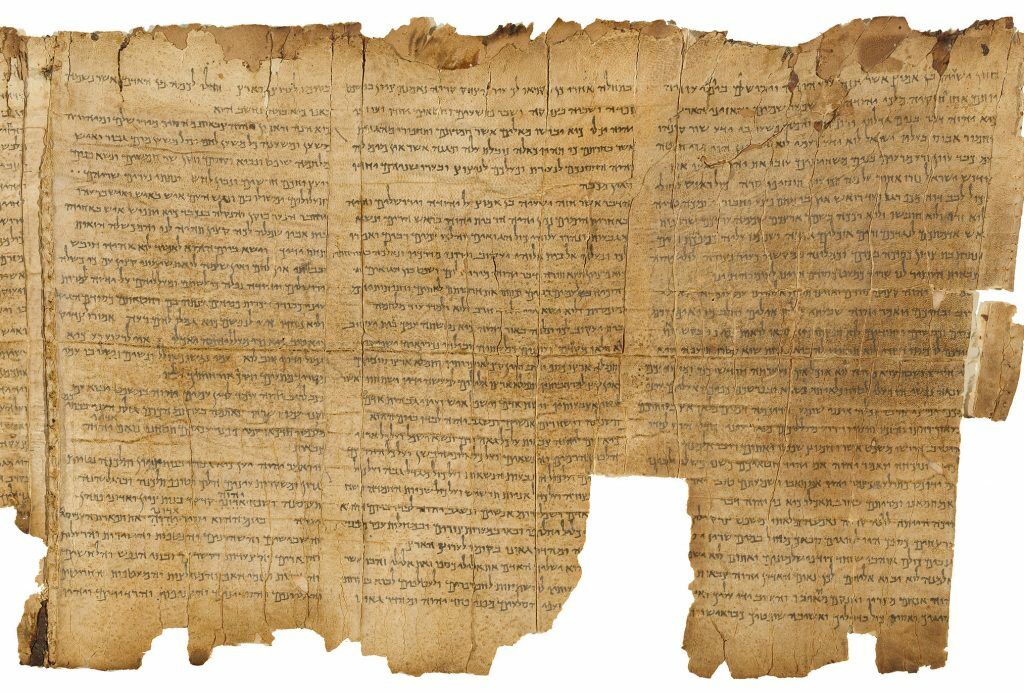

Our earliest complete version of Isaiah is from the Dead Sea Scrolls, dating to c. 125 b.c.e. While critics vie for a later-than-traditional date for the book of Isaiah, even this full-length scroll dates well before the fulfillment of a plethora of Isaiah’s prophecies—many of which have since come to pass, and many others yet to be fulfilled. In fact, Isaiah himself acknowledged that his book was written primarily to be preserved for the end-time, when the main part of the prophecies would be fulfilled! (In Isaiah 30:8, “time to come” should read “latter day.” Jeremiah and Daniel also did the same—see Jeremiah 30:1 and Daniel 12.)

The first-century c.e. historian Josephus states that the prophesied King Cyrus, when he came on the scene in the fifth century b.c.e., actually read of the advance prophecies in Isaiah in which he was specifically named (Isaiah 44:27-28; 45:1-4). (Incidentally, Josephus also wrote that Alexander the Great was shown the prophecies of his reign in the book of Daniel when he arrived in Jerusalem in the fourth century b.c.e.—hence the favorability he showed to the Jews.) These points all add accumulative evidence for the early traditional writing of Isaiah.

When trying to re-date the book of Isaiah to later ghostwriters, a plethora of textual and historical problems arise. When accepting the book as written by Isaiah, on the other hand, no problems arise—unless you don’t believe in prophecy.

The Book of Ezekiel

Traditionally dating the book of Ezekiel is not hard: Dates are given throughout the book for when certain visions were received (during the early sixth century b.c.e. captivity); and virtually the entire book was written in a single-person, autobiographical style.

The contention with Ezekiel is, as usual, the prophecies—hence some dating it to the fourth to third centuries b.c.e. Remarkable prophecies are contained throughout the book of Ezekiel, such as the downfall of Tyre. This occurred spectacularly about 250 years later, during the fourth century b.c.e.

Ezekiel was written (if we are to go by the traditional dates) within a much shorter time period than Isaiah—within 20 years—but likely compiled in continuous form, rather than being pieced together here and there. There is a lot of repetition and unity throughout the text. Ezekiel shows knowledge of earlier works, such as the Torah, and even mentions the Prophet Daniel, who (according to traditional dating) was on the scene at the time. (This poses somewhat of a problem for scholars who try to re-date Daniel to the second century b.c.e., but yet claim Ezekiel as a fourth-century work. We’ll cover Daniel in our next article in this series.) Ezekiel’s Hebrew also shows a transitional style in the language—not totally of the early classical style (such as Isaiah), but not totally of a late style. This transitional style fits perfectly with the traditional date of Ezekiel being on the scene.

Actually, due to the writing style and setting of Ezekiel, many scholars do accept that the book is authentic. But a large number of them believe that later annotations were made by later writers, thus explaining away some of the prophecies contained within its pages. But could this have really have happened? Perhaps on a small scale in isolated communities, adding their own thoughts—but to the central chief Jewish religious system, controlling the sacred books? Would they really have allowed the original text to be messed with, and then become accepted and disseminated as sacred? The Jews, to this day, are famously pedantic about these things—preserving every original “dot” and “tittle”—and rightfully so!

Josephus provides confirmation, alongside Jewish tradition, that the entire Hebrew Bible was finished and canonized during the fifth century b.c.e. This effort was driven chiefly by Ezra. During and beyond this period, there was a strict, fully established Jewish religious authority carefully governing Scripture. This is known in secular history. It is known in the New Testament, where it is stated that the Old Testament scriptures were all accurately preserved at the hand of the Jews (Romans 3:1-4, 2 Timothy 3:16-17). The idea that “pseudo-writers” would try to slip spurious works into the collection of revered, painstakingly copied, and preserved original scrolls is absurd.

Actually, it’s already been tried. It’s called the Apocrypha. Its name means “hidden” or “spurious”—for good reason. The centralized religious authority was there to keep these kinds of works far away.

The above was a sampling of the major prophets. Let’s take a brief look at some of the minor prophets. Much information from this section is based on research from Craig Davis’s fantastic book Dating the Old Testament (see here).

The Book of Amos

Amos is an easy prophet to place in terms of dating. He lists the kings that he was contemporary with—alongside an interesting phenomenon. Amos undertook his writings “two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1).

Based on the reign of the kings, the book of Amos is traditionally placed between c. 790 and 750 b.c.e. But we can be more specific, because, as Amos described, a massive earthquake took place throughout Israel in c. 760 b.c.e. This absolutely catastrophic earthquake has been witnessed in multiple archaeological sites in and around Israel. Occupational layers from this time period show evidence of collapsed floors and tilted walls. Experts have even been able to guess, from the evidence, the size: around 8.2 in magnitude!

Furthermore, Amos describes an Israel at a time of prosperity and wealth—before the setback and fall of the nation toward the end of the eighth century b.c.e. Earlier Hebrew words are used within this book, consistent with dating it to the traditional, eighth century b.c.e. time period. Specifically, if the great earthquake did occur in 760 b.c.e., then Amos’s writings can be dated to 762 b.c.e. And then, just as he prophesied, the downfall of Israel spectacularly occurred 40 years later.

Jonah

The book of Jonah is a unique case, because its message is intended for the Gentile Assyrians. Traditionalists say that it was written by Jonah, circa eighth century b.c.e. Some minimalists believe that it was written around 450 b.c.e., as a sort of “angered response” to Ezra and Nehemiah forbidding interracial marriage with Gentiles.

As much of a stretch as that is, what clues does this book provide? It contains a somewhat detailed description of the Assyrian city of Nineveh. The Bible describes Nineveh as a massive city of “three days journey” in size (Jonah 3:3). Archaeology shows that Nineveh plus its suburbs was about 60 miles across—equating to 20 miles of walking per day, or three days’ journey. Excavations have revealed that the city proper of Nineveh was an area of at least 1,730 acres—allowing plenty of room for the 120,000 residents (Jonah 4:11).

Davis writes on the accuracy of Nineveh’s population figures given in the book of Jonah:

An ancient Assyrian inscription indicates that the city of Calah, Assyria, which was not as large as Nineveh, had 69,574 inhabitants in 879 b.c. This would mean the Jonah 4:11 population of Nineveh (120,000), 100 years later is in the right ballpark.

Regarding the geographical accuracy, he continues:

Jonah left Nineveh and watched it from the east (Jonah 4:5) [this was an unusual direction if he had merely been intending to return home to Israel]. Nineveh was located on the east bank of the Tigris River, with hills east of the city. This would give Jonah a good vantage point to view the city, as well as an early view of any enemy army [that Jonah would have expected to fulfill the curse—Jonah 3:4], which would need to approach Nineveh from his side of the river. These points of accuracy would seem unlikely in a post-exilic allegory.

Then there are other accurate details in the book of Jonah, such as the statement that the Assyrians caused even their animals to mourn (Jonah 3:7-8). The Asiatic tradition of having their animals participate in mourning is recorded by the fifth-century b.c.e. historian Herodotus.

Further, the writing used by Jonah indicates an authentic style. There are no Persian words—as would be expected from a later work—and the use of a small number of Aramaic words points back to the sailors on Jonah’s ship, who themselves likely spoke Aramaic. Thus, the extant evidence points to the traditional dating of around 760 b.c.e. If postexilic frauds had so accurately written this book 300 years later, it would have been as great of a miracle as Jonah in the giant fish!

The Book of Haggai

The Prophet Haggai is perhaps the most uncontested Old Testament writer of all. Virtually everybody considers his book to be legitimate, dating to around 520 b.c.e., just as the book details.

We cover it here because of what it can tell us about other books of the Bible—particularly the Torah.

Haggai shows a familiarity with the Torah, such as the laws of purity (Haggai 2:11-14). However, according to the main scholarly “documentary hypothesis” for the writing of the Torah, these laws were not supposed to have been penned for another 20 to 100 years, by a fraudulent “P Writer,” after Haggai. If that were true, they could not have been accepted tradition and knowledgeable practice to Jews such as Haggai. Thus, Haggai helps prove an early dating of the Torah, and helps show just how tangled and self-effacing the theories of the critics are.

Haggai is clearly dated to the period just before the temple is finished, during the reign of Darius i—and even the dates of his writing can be estimated with fair accuracy: August 29, October 17 and December 18.

It Only Makes Sense

As it turns out, there is evidence to say that it makes sense for the early, traditional authorship of the Prophets. Those who take it apart are doing so with no hard evidence to go on. Primarily, they are doing it because of their own conviction that these prophecies couldn’t have been made in advance. But there is no extant evidence to say that the Prophets couldn’t have been written when the text describes. And there is a lot that says they should have been.

Of course, believing in the literal account means believing in prophecy. It means believing in a God who is capable of predicting the future. A God who declares “the end from the beginning, and from ancient times the things that are not yet done, saying, My counsel shall stand, and I will do all my pleasure” (Isaiah 46:10). And that is a step way too far for the critics—and it seems no amount of evidence can change that.

As time goes on, the evidence continues to mount for the early, traditional authorship of the Bible. We’ll see that as we continue our series, looking next at the third part of the Tanakh: the Writings.