Baby’s Gold Ring? An Intriguing Historical Connection to Dr. Mazar’s ‘Final Discovery’

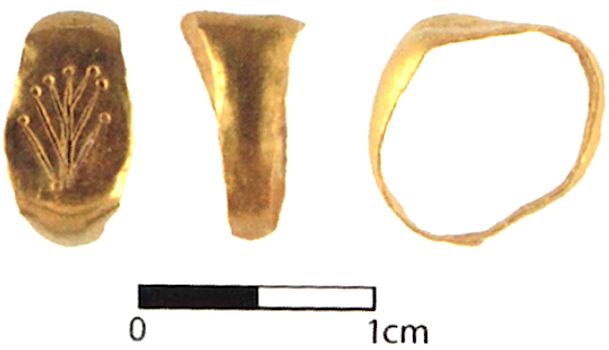

It was the final release of an artifact made by Dr. Eilat Mazar, less than two months before she died: a 2,000-year-old miniature gold ring, etched with a seven-branched menorah symbol. Due to its miniature size, Dr. Mazar pointed out that it “could fit only the finger of a newborn.”

While the discovery was only released to the public for the first time in April, it was originally uncovered some 50 years ago, during the Temple Mount “Big Dig” excavations of her grandfather, the famous Prof. Benjamin Mazar (Eilat was a young girl working on the dig site at the time). Professor Mazar died before completing full publication of his massive decade-long excavation effort—as such, his granddaughter took on the task as her own. The discovery of the ring was revealed through the publication of her latest book, Over the Crossroads of Time: Jerusalem’s Temple Mount Monumental Staircases, as well as in the reporting of aiba correspondent Brent Nagtegaal.

The ring, less than 1 centimeter in diameter, had been found by Professor Mazar’s team buried within a Herodian layer, inside a vault located outside the Temple Mount walls. It was roughly dated to around the early first century c.e.

It is a gem of a discovery. But a baby’s ring? What would a Jewish newborn of this period want with golden ring?

Dr. Mazar was known among fellow archaeologists for her ready consultation of the Hebrew Bible in aiding the interpretation of her discoveries. And fittingly, this latest discovery goes together with a peculiar passage of Scripture. (Dr. Mazar did not make the association in her publication, and understandably so: Hers was a brief summary of the discovery, and this passage is not from the Hebrew Bible—rather, it is from the first-century New Testament.)

The Book of Matthew, chapter 2, describes the arrival of the “wise men” from the East to visit the newborn Jesus. “Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem. … And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh” (verses 1, 11).

The Greek word used here for gold can mean things made of gold, gold ornaments, stamped gold. Another New Testament passage, 1 Timothy 2:9, uses this word to refer directly to gold jewelry.

Here, then, is a biblical account of a Jewish newborn, during the Herodian period, being gifted some sort of precious gold trinkets. And this parallels well Dr. Mazar’s discovery of a Jewish symbol on a newborn-sized ring, dating to the Herodian period, made of gold.

The first-century textual account is a parallel to the on-the-ground discovery. This “baby’s ring,” paired with this historical biblical account, surely attests to a practice of gifting newborns (of rich or royal descent) with precious jewelry.

Other ancient infant and child rings have been discovered throughout antiquity (including with Jewish motifs), often made of poorer-quality metal such as bronze. But this exceptionally small ring, made of gold, and including this famous Jewish symbol, is an especially fine example.

A similar-style gold ring with menorah motif, dating to the same first-century period, appeared in an auction in London in 2011. This too was a very small ring, although still a third larger than Dr. Mazar’s—evidently intended for an older child. It is a good parallel in dating, design, material and overall small size in general.

Of course, it cannot be proved that this baby’s ring belonged to Jesus himself (still, it is worth noting that he is repeatedly symbolized in the New Testament together with the seven-branched menorah, and that his family regularly brought Him to this temple area in Jerusalem as a child—Luke 2:41). But the association with the scriptural account is notable, establishing an ancient precedent and at least giving a representation of what the newborn could have received as a gift from the “wise men.”

This “final discovery” released to the public from Dr. Mazar—really, from both Eilat, “queen of Jerusalem archaeology,” and her grandfather, Benjamin, “dean of biblical archaeology”—is a tiny testament to nearly a century of archaeology work, uncovering the rich history of the Holy Land.

And on a personal level, I think this final discovery is really special, because although Dr. Mazar’s own physical “light” went out weeks after the announcement, the symbol of the menorah is one of a continually burning flame, a continual divine work (Exodus 27:20). I think this is a little symbol that her light will keep burning, that this work of excavating Jerusalem in her unique, Bible-based approach—as she described herself, “the Bible in one hand, and the tools of excavation in the other”—will continue.