Evidence of King Solomon Found—in Spain! An Interview With Sean Kingsley

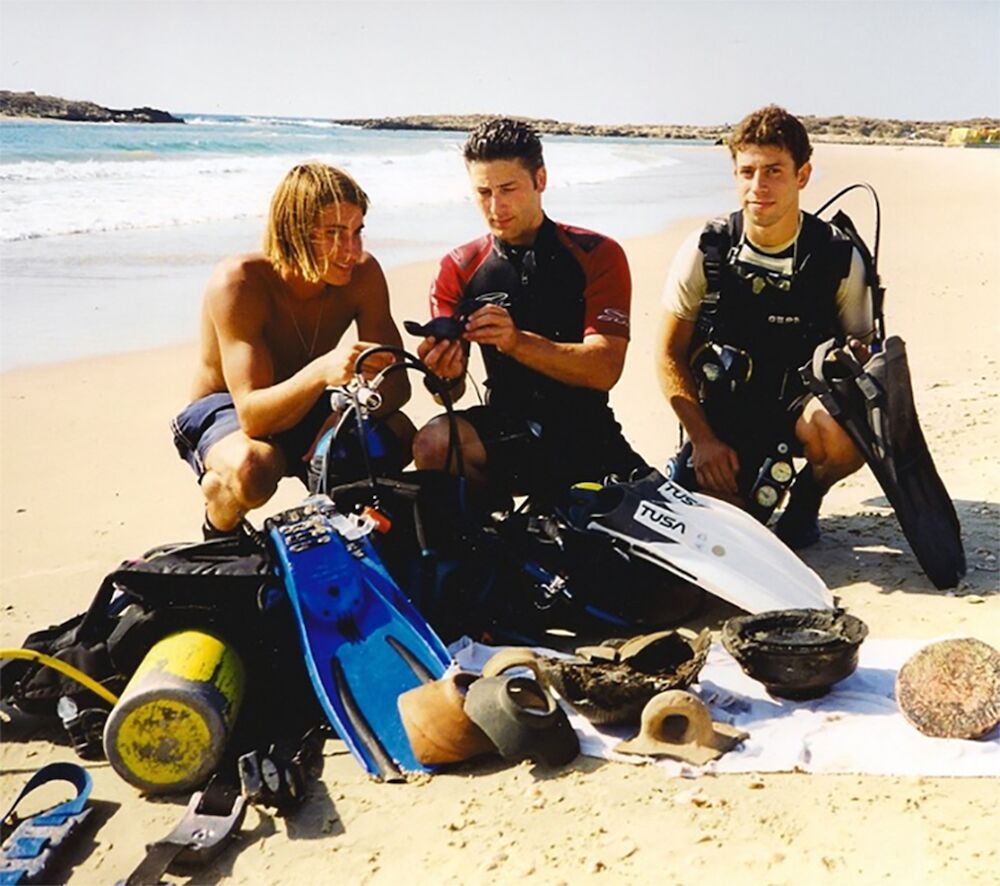

Dr. Sean Kingsley has been diving in Israel’s coastal waters since he was a teenager. Decades later, his passion for underwater discovery inspired him to start Wreckwatch, a quarterly magazine created to spotlight the forgotten history lying on the world’s ocean beds (wreckwatchmag.com).

In the Spring 2021 issue, Dr. Kingsley shares evidence from both underwater and above-ground excavations that shows King Solomon presided over a maritime trade empire. The Bible records that, together with the Phoenicians, Israel’s 10th-century b.c.e. king presided over a vast commercial empire, one that included a network of mines, ports and ships, including a large port in Tarshish (1 Kings 10). Thanks to this powerful trade empire, King Solomon acquired unparalleled gold and silver, as well as all kinds of exotic materials.

In May, Dr. Kingsley discussed his findings with Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology assistant managing editor Brent Nagtegaal. Following is the interview, lightly edited for clarity.

Brent Nagtegaal: Thank you for taking the time to meet with me. So how did you get into marine archaeology?

Dr. Sean Kingsley: When you are young, you sort of meander a bit as you try to find something that will turn you on. I was interested in history when I was 16 to 17 years old. But it frustrated me because in the UK it was all about kings and queens, and empires and colonies. I thought, Where’s the little guy? Where’s the small currents between the coronations, weddings and murders?

Between what we called O levels and A levels, my parents kicked me out of the house. They sent me to Israel to experience the Kibbutz life. I ended up in a place called Kibbutz Ma’agan Michael, which was an absolutely stunningly beautiful place overlooking the sea. One day we took a tour to a little museum. There we met a museum director named Kurt Raveh, a Dutchman who had lived in Israel for many years. He had his kid on his shoulders and waxed lyrical with great charisma. I asked him, “Do you take volunteers?”

He gave me this spiel, “Come and join us. We dive, open tombs.” The little Indiana Jones on my shoulder said, “That’s for me.” And it all sprung from there.

BN: How do you become a marine archaeologist? Do you start with regular archaeology, and then get into underwater archaeology?

SK: I did land and sea. For anyone who is interested in getting into marine archaeology, you have to learn the basics: soil archaeology, dirt archaeology. It teaches you the method, but more importantly it teaches you how to think. You have to go to a site with a pure set of questions–certainly in marine archaeology. I always say, “Ships don’t sail in a cultural vacuum.” I’m interested in connecting all the links from the farmers in the field to the ports and the warehouses, and then shipwrecks.

BN: In the latest issue of Wreckwatch, you have an article titled “Seeking Solomon’s United Monarchy on the High Seas.” In the article, you connect some of your finds with King Solomon, who the Bible says had a large navy and a vast trade empire, including gold and silver mines. What does the Bible have to say about this period, and why did you expect to find a Solomonic era mine as far away as Spain?

SK: If you had come to me 20 years ago and said, “You know King Solomon? We have evidence of him on the far side of the moon, effectively—5,200 miles away,” I would have dismissed it. As you Israelis put it, “shtuyot b’mitz agvaniot” (“nonsense in tomato juice”).

I first began to think about Solomon when diving off Dor, which was known to be one of the 12 administrative regions of the king. There is a monumental, two-chambered gate on Tel Dor. And you could smell the past. But could you smell Solomon? Then we went diving off a set of islands and one of them was named Taphat, which was the princess daughter of Solomon. When you see these things, your mind wonders, “What if this is possible?”

I approach this purely from a historical perspective. I don’t feel a need religiously to prove that Solomon existed. I’d like to know what the science and archaeology say. The Bible says that he built an enormous temple and palaces in Jerusalem. It says Solomon made silver as common in the Holy City as stone, and it refers to him putting 7,000 talents of silver on the temple wall (which would equate to 260 tons of silver). I always believed figures like that in the Bible were exaggerations. But the question within the myth is, how much of it is truth?

My job is how to unpick those threads. If King Solomon had all this wealth in Jerusalem, where did it come from? And if he had all this silver, gold, and if he had gone to the lands of Ophir and Tarshish in search of gold and silver, apes, peacocks, as the Bible says, then this must have required a web of infrastructure. There must have been ports, warehouses and ships. And where ships sail, you’d expect there to be shipwrecks.

Now, from history and archaeology we know that Tarshish must have been somewhere very far away. We know from Assyrian texts that Tarshish was somewhere on the opposite side of the Near East. Many years ago in Sardinia, at a place called Nora, an inscription was found on a meter-long stone that refers to the Phoenicians fighting in that part of the world. This is interesting, because the Bible famously says that King Solomon effectively entered into the world’s first special relationship in a trading venture with King Hiram of Tyre in Lebanon. Together they pooled forces and went out to try and find these riches beyond the coast of Israel.

BN: So the Nora tablet found in Sardinia is one piece of evidence proving the Phoenicians were in the Western Mediterranean around the time of King Solomon?

SK: Yes, in the ninth century. I use the Phoenicians as trace elements. I see Solomon as sitting back in Jerusalem, as a kind of oil magnate-tycoon. He stayed in Jerusalem and bankrolled everything. But then you also have the archaeological visibility issue. Phoenicians were shipping purple dye and wine. What was Judea specializing in? Sweets, honey, olive oil, wheat—the kind of things that you are not going to necessarily find in shipwrecks. The reason we find wrecks is because of heavy stone anchors, amphoras and cannons that seal hulls in place. Light organic Judean goods are less likely to survive underwater.

So what you’d be looking for then is a place where the Phoenicians and Near Eastern material culture overlap with massive evidence of mining of silver in a place which may or may not sound like Tarshish.

BN: Why did you decide to visit the southwest coast of Spain? What made you think ancient Tarshish might be located in Spain?

SK: We Brits do a lot of holidaying in southern Spain. I remember on one occasion, there was a new development in a museum in downtown Cadiz. When they were excavating the foundations of the Teatro Comico, they hit some ruins. When they started to excavate the ruins they uncovered, no joke, a series of houses on terraces and then skeletons. It was a murder scene. A home caught fire and somebody died failing to escape. They did dna analysis on the bones and were rather shocked because on the father’s side, there was a direct link with Phoenician dna. And the site was rich in Phoenician pottery too. So you have these remains dating to 820 b.c.e. This is early. It’s not Solomon’s period—he lived between 970 and 930 b.c.e.—but it gets the mind thinking.

So I did a lot of bookwork and research, and then decided to take myself off one summer to the Andalusia region in Spain to start looking at a number of settlements. When I started digging around, I found that Near Eastern or Phoenician remains are really very prevalent all the way from Huelva in the west to Alicante in the east, which is an arc of some 690 kilometers [430 miles]. So we have to imagine a sort of modern Costa Del Solomon, or a Costa Del Phoenike. Then the question is, how far back in time can we trace these Phoenician remains?

BN: And this led you to one of the most famous rivers and mining areas in the world, Rio Tinto?

SK: Yes. Rio Tinto is 65 kilometers [40 miles] upriver from Huelva in Spain, which is situated on the coast of the Mediterranean. Rio Tinto was the biggest mine in antiquity and most famous in the Roman period. It is still being mined today. There is a little museum there with some Phoenician pottery.

I started researching where this pottery came from. I learned that there was a hill in the middle of this area. Many decades ago, archaeologists from both Israel and Spain found shafts that were excavated inside the hills. And on the top of it, they found a 900-meter-wide village. When they dug this up, they were amazed to find that it was very early, around 820 b.c.e., and was stuffed with Phoenician pottery. Around 30 percent of the pots and pans were Near Eastern. And some of the Phoenician pottery was actually fused to remains of silver. Next to it were stone hammers and grinding tools for processing the metal. It was clear that this was some kind of frontier town used on a seasonal basis to extract silver. And the local manpower included Phoenician workers.

From Rio Tinto, I started looking again at ancient literature and other sources. I found that in the 17th century the Spanish actually called this place “Cerro Solomon,” or the Hill of Solomon. This shows that in local legend and myth there was an association with massive mining and King Solomon.

Now if the silver was being mined at Rio Tinto, or Solomon’s hill, I believe it was being turned into ingots in Huelva, which is on the coast. Huelva was known in this period as Tartessos, which we believe was the Greek version of Tarshish. And that closes the loop.

BN: Archaeological excavations have also been performed at Huelva. And the remains here have been dated closer to King Solomon’s time?

SK: Yes. And this is absolutely crucial. The discoveries at Huelva take you back 100 years earlier than those found at Rio Tinto. Now we are much closer to the time of King Solomon.

In Huelva, there is a massive statue of a local lad done good. It was from the shores of Huelva that Christopher Columbus, irony of ironies, set out for the Americas. If you look at his writings, he actually believed he was going out to find El Dorado and what he believed was King Solomon’s gold. So you’ve got this irony of Columbus setting off from Huelva in search of Solomon’s gold, when actually under this statue was ground zero of where Solomon’s wealth may have come from. He should’ve really checked his history!

BN: So Huelva was a transit point for the silver?

SK: Yes, exactly. Rio Tinto and Huelva are linked by a river, the Coloured River. And Huelva is on the coast and is a port city. And then the international shipping trade port was Cadiz [about 60 miles south]. So you have three hubs.

When they started excavating at Huelva, they found massive furnaces and sandstone molds for processing silver. And again lots of Phoenician pottery—40 percent of the pottery there was Near Eastern, or Phoenician. And next to it, the kind of goods we know the Near East specialized in. There was both ivory, raw and finished products. They also found murex shells—the royal purple, which is very much associated with the Bible—and which the Phoenicians were expert in processing. Parts of shipbuilding turned up—mortise and tenons used in making ships. And finally the date: at least 900 b.c.e. And according to this chronology, perhaps as early as 930 b.c.e., which overlaps precisely with the end of King Solomon’s reign.

BN: Were you surprised when you found tangible evidence of the Solomonic period maritime trade with the Phoenicians?

SK: I didn’t go seeking out to prove a theory. I was open-minded. I was surprised. It is now not just Andalusia where the trail runs hot. In Carthage, they have discovered Phoenician artifacts that have been radiocarbon dated to 900 b.c.e.

BN: Has your discovery of Solomon’s period generated much interest from the international press or media?

SK: Yes. This story on Solomon just went through the roof, which really did surprise me. tv and radio companies came knocking. I must now put out a scientific report. And there is lot more to uncover and understand.

I will leave you with just a tantalizing bit. If any of your friends in Israel or visitors find themselves out on a limb in Israel when tourism opens up again, head down to Tel Dor. There is an amazing national park, walk around, smell the ruins, get in touch with my friends at the dive center at Northern Wind. Try to find Kurt Raveh to give you a tour of the place. If you are lucky, Kurt will tell you his latest story, which I will share with you very briefly.

Kurt was walking with his dog after a storm. Because the ancient port is shallow, you can see where the sandbanks have been carved out by enormous weather patterns. And when you see darkness, you know the seabed has opened up. There are 28 shipwrecks at Dor. Everything you want: Phoenician remains, there’s stuff from Bronze age, early Iron Age, masses of Byzantine and Ottoman. But nothing from this iconic United Monarchy period.

Kurt’s dog went swimming in the sea, but suddenly was walking on water. This perplexed Kurt. He put on his snorkel, went down and found an enormous, 2-meter stone anchor. He also saw timbers coming out of its sides. Kurt took some of them out, thinking, “Here we go again, more Ottoman or Byzantine stuff,” and sent it off to Switzerland for testing. Guess what? The radiocarbon dating placed them in the 10th century b.c.e. So it is very possible that where it all started at Dor, one of King Solomon’s administrative centers, perhaps, just perhaps, in the future we will find the first shipwreck associated with this immortal king.

BN: I’ve just gone through the Spring 2021 issue of Wreckwatch magazine. It is a massive magazine with lots of interesting information from the ancient underwater world. What is your plan with the magazine, and how can people get to it?

SK: With Wreckwatch we are trying to create that sense of awe and beauty that Jacques Cousteau created. When you get to Israel, everyone knows about the Holy Land and how the Bible played out across the holy soils. But I think a lot of people still don’t know there is such a rich legacy and maritime tradition, which has appeared in around 500 shipwrecks beneath the ocean.

We wanted to talk to the pioneers who are in their 70s and 80s and to the next generation of students and bring them all together. It was supposed to be a good 70-page magazine, but ended up as a whopping 165 pages. It is free to everyone. We use it for education and entertainment. Go to wreckwatchmag.com. Sign up and plunge in.