Were There Giants in Canaan After All?

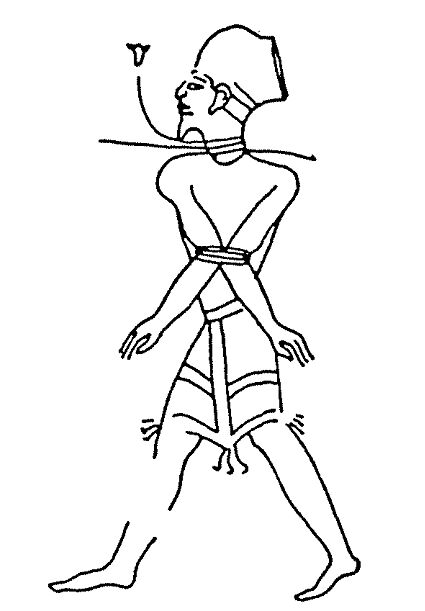

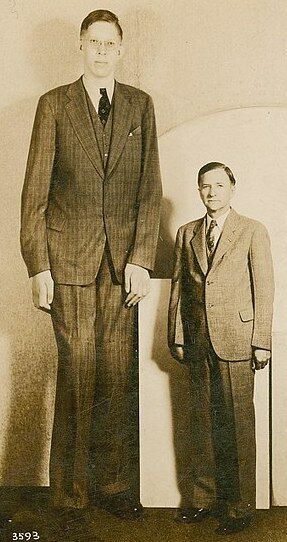

The Bible is famous for its account of Levantine giants. Goliath was “six cubits and a span,” or over 9 feet tall, according to 1 Samuel 17:4. The giant Og’s 13-foot-long bed actually became a “museum piece” in the biblical account (Deuteronomy 3:11). An Egyptian mercenary is described as being 7½ feet tall (1 Chronicles 11:23). Tall tribes—Anakim, Nephilim, Rephaim—terrified the Israelite spies scouting the Promised Land; the spies over-dramatized them as making the Israelites look like “grasshoppers” in comparison, to persuade the Israelites to turn back to Egypt (Numbers 13:33).

“Giants in Canaan” are easily passed off as fanciful biblical myths. But did you know that there is contemporary material detailing the existence, and even heights, of “giants” of the Levant?

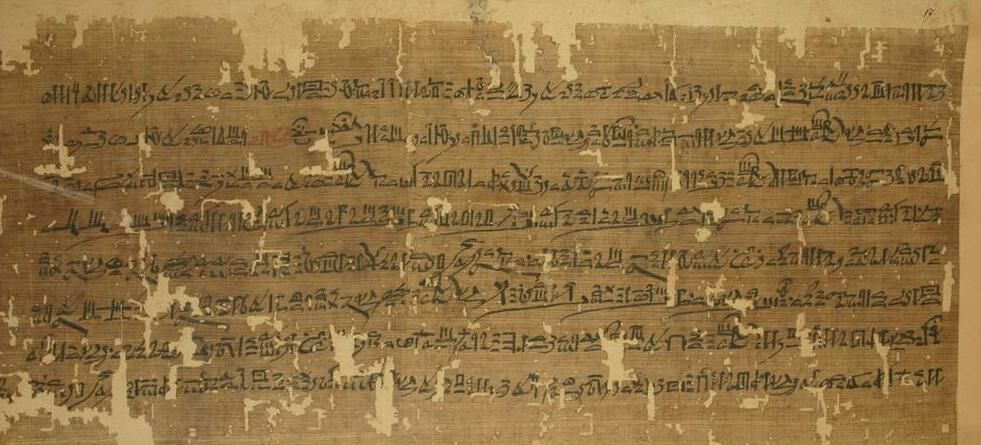

Papyrus Anastasi i is an Egyptian literary text from the 19th Dynasty (around the 13th century b.c.e.). It is a “scribal training” sheet that includes numerous important historical details about the early Levant, including the names of towns throughout Canaan and Syria.

The text mentions a Levantine tribe called Shasu and its warriors: “The [valley region] is infested with Shasu … some of them are of four cubits or of five cubits, from head to foot, fierce of face, their heart is not mild, and they hearken not to coaxing.”

That may not mean anything to a modern reader, but to Egyptians familiar with their royal cubit length, that was a truly impressive size. In modern terminology, four to five Egyptian cubits is from just under 7 feet to 8 feet, 7 inches tall.

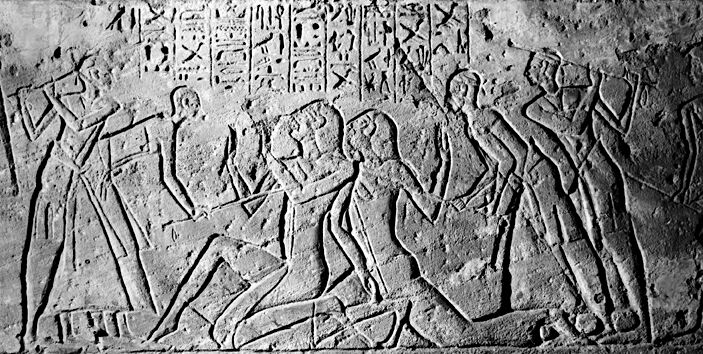

There is also the depiction of Shasu captives on an Egyptian wall relief depicting the Battle of Kadesh (circa 1274 b.c.e.). It shows two captured Shasu spies being beaten by a horde of Egyptians. Often in such ancient artwork, national dominance was shown by the size of the individuals depicted (note the classic examples of massive pharaohs defeating their enemies). But this Kadesh image depicts, in very realistic style, large Shasu males compared to their victorious Egyptian counterparts. Thus, together with Papyrus Anastasi i, highlighting members of Shasu society as reaching very tall heights.

Still, little is known about the Shasu people. The earliest-known reference dates to a Levantine peoples-list from the 15th century b.c.e. We know from 13th-century b.c.e. Pharaoh Merneptah’s inscriptions that they were on the scene at the same time as the early Israelites. Egyptian artwork depicts them dressed in a clearly Canaanite manner. The Kadesh Inscriptions relate that they served in a limited mercenary sense alongside the Hittites.

Thirteenth-century b.c.e. Egyptian texts relate six different tribes of Shasu. Perhaps all or only certain of them were predisposed to reach tall statures. Whatever the case, they lived specifically in the southern Levant, in the region of the Philistines, Canaan and Transjordan (thus fitting with the biblical locations of “giant” peoples). They also disappear from the archaeological record during the Early Iron Age (late biblical judges-early kings period)—the same time in which the biblical references to them end.

The association by the Anastasi papyrus with a Levantine valley region is interesting given the Bible specifically highlights a Valley of Rephaim (one of the “giant” tribes), famous to this day as the bustling Emek Rephaim, which descends from Jerusalem.

There are several other extra-biblical references. The early-second-millennium b.c.e. Egyptian Execration Texts name the “people of Anak,” the same title given in the Bible (Numbers 13:33; “Anak” meaning “giant”). And as for the biblical giant Og, he is referenced in a later, circa 500 b.c.e. Phoenician inscription as “the mighty Og.”

Og was a king of the Rephaim, based at “Ashtaroth and Edrei” (i.e. Joshua 13:12). A circa 1200 b.c.e. Canaanite tablet from Ugarit mentions a deified great king Rapiu, a name etymologically linked to Rephaim (in the singular form). “May Rapiu, King of Eternity, drink wine … the god enthroned in Ashtarat, the god who rules in Edrei.” The combination of names Rapia, Ashtaroth and Edrei are a remarkable link to the biblical account of Og and the Rephaim. Could it even be a reference to this king himself? It has been suggested that “Og” was simply a regnal title meaning “man of valor,” paralleling other Ugaritic and Canaanite titles. The list of extra-biblical parallels could go on.

It’s easy to pass off some of the earliest biblical accounts as simple myth. But even when it comes to giants, the biblical record holds alongside the archaeological evidence.