Uncovering the Battle That Changed the World

It’s one of the most fascinating and gripping stories in the book of Genesis. It’s also the earliest account of warfare in the Bible. In Genesis 14, four powerful eastern kings ally against an inferior force of five Levantine kings. The smaller city-states are easily defeated, and the people captured, including the nephew of Abram (later named Abraham).

What happens next is so astounding, most people reject the tale as fiction. The patriarch Abram rallies 318 of his servants and vanquishes the Mesopotamian juggernaut. The captives, including his relatives, are freed, and Abram returns to Canaan with tremendous fanfare.

Many scientists and academics question this story. Bible scholar Mary Jane Chaignot wrote that the story “is almost monotonous in its detail of names and places, none of which can be verified by outside biblical sources. That makes scholars nervous. … [I]t raises many unnerving questions about the historicity of the whole chapter. Like, maybe it really isn’t true, after all” (BibleWise; emphasis added throughout).

Prof. Ronald Hendel agrees: “The current consensus is that there is little or no historical memory of pre-Israelite events or circumstances in Genesis” (The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation).

These bold claims simply are not true. A broad body of evidence supports the history recorded throughout the book of Genesis, and specifically, the true “World War i” in Genesis 14.

Setting the Scene

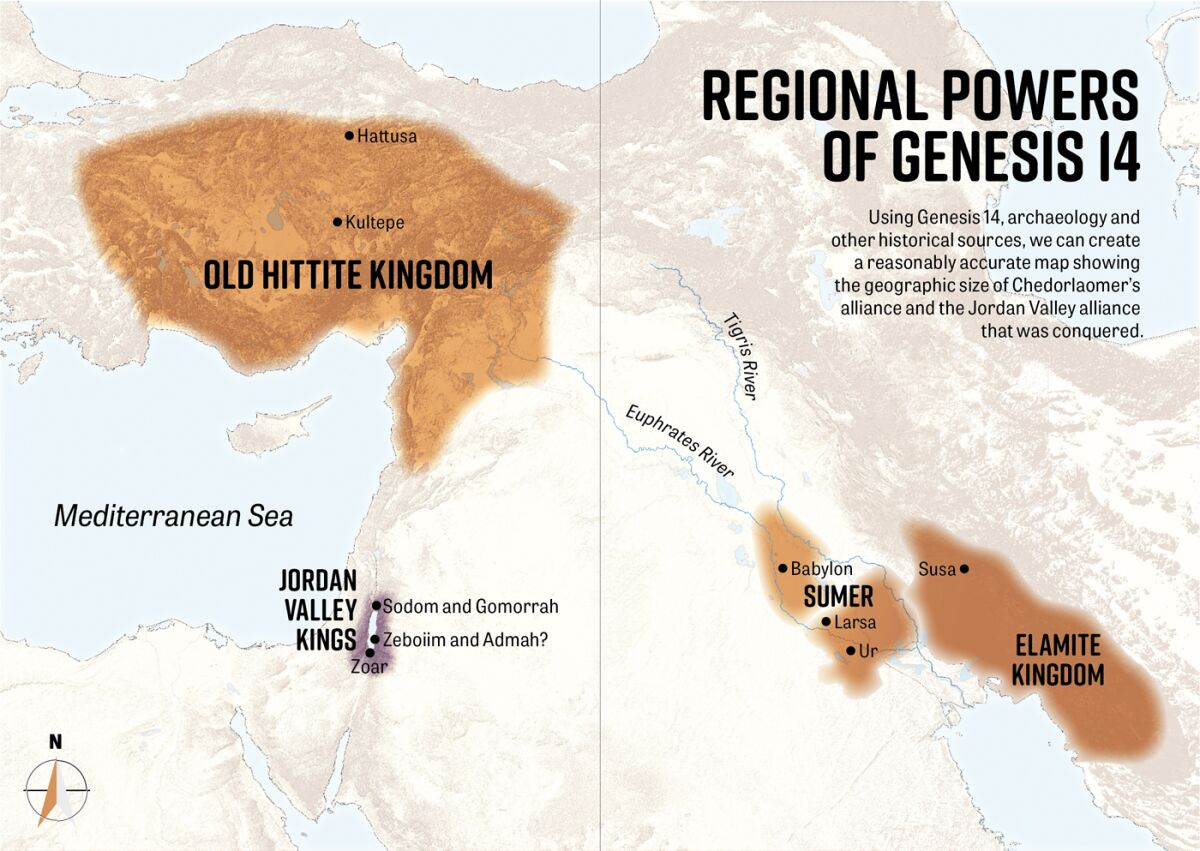

According to the biblical account, the Jordan Valley was subject to Chedorlaomer, king of Elam. His vassal territory included five small kingdoms, namely Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboiim and Zoar (Genesis 14:2-3). The local monarchs of these kingdoms were “servants” to the Elamite king and paid him regular tribute. One of the key characters in Genesis 14 is Abram’s nephew Lot, who had recently moved to the land of Sodom.

In the 13th year of their oppression, the five valley kings rebelled against their Elamite oppressor. In response, Chedorlaomer formed a coalition with three other regional powers and marched on the Jordan Valley, determined to beat the rebels into submission.

Genesis 14 lists the names of both sides of this conflict. The aggressors, led by Chedorlaomer, included Amraphel, king of Shinar; Arioch, king of Ellasar; and Tidal, “king of Goiim.” The Jordan Valley alliance included Bera, king of Sodom; Birsha, king of Gomorrah; Shinab, king of Admah; Shemeber, king of Zeboiim; and an unnamed king of Bela, or Zoar.

Biblical chronology places the events of Genesis 14 sometime during the start of the second millennium b.c.e., around the 19th century. Historians debate about the precise dating and chronology of the remains relating to this event. They also debate the exact identity of the kings listed in Genesis 14, but their names and nationalities match known polities during this general time period.

The Enemy Juggernaut

Chedorlaomer’s Elamite empire, situated in what is now southwest Iran, was a well-known, well-established entity during this period. And the name Chedorlaomer is a recognized Elamite name, Kudur-Lagomer.

“Shinar” is the biblical name for Sumer (pronounced Shumer), the Mesopotamian kingdom of the Sumerians. (This kingdom is regarded as the “earliest-known civilization,” a description confirmed in Genesis 11:1-2.)

Sumer included the famous city of Babylon. The Sumerian kingdom eventually became known as the Babylonian Empire. The name of the leader of the Sumerians, Amraphel, is notably Semitic.

The kingdom Ellasar most likely represents the Mesopotamian kingdom of Larsa, which emerged as a power player for a short window during the early second millennium. Arioch, king of Ellasar, was a name common in north Mesopotamia. Arioch may be positively identified as the final king of Larsa, Rim-Sin i, whose Semitic name is Eri-aku.

Finally, there is “Tidal, king of Goiim.” The polity here is ambiguous (the Hebrew Goiim meaning “nations” or “peoples”), but Tidal is a recognized Hittite name, Tudhalia. Several Hittite rulers bore this name. The Hittite empire was based in modern-day Turkey and was comprised of numerous tribes and peoples, thus befitting the name “king of nations” or “peoples.”

As for the five kings in the Jordan Valley, they are not mentioned in historical or archaeological records; these were small city-states, not large empires like those that bore down on them. However, the city-state of Sodom has been identified by archaeologists as Tall el-Hammam (sidebar at the end of this article, “Rise and Fall of Sodom”). The city-state of Gomorrah is believed to be one of the many unexcavated ancient settlements near Sodom. The exact location of Admah is uncertain, but there is an apparent mention of this city in the Ebla Tablets (dating a few centuries before this war). Zeboiim is also unknown. The twin-named city-state Bela-Zoar has been identified as the archaeological site Zoara in southern Jordan.

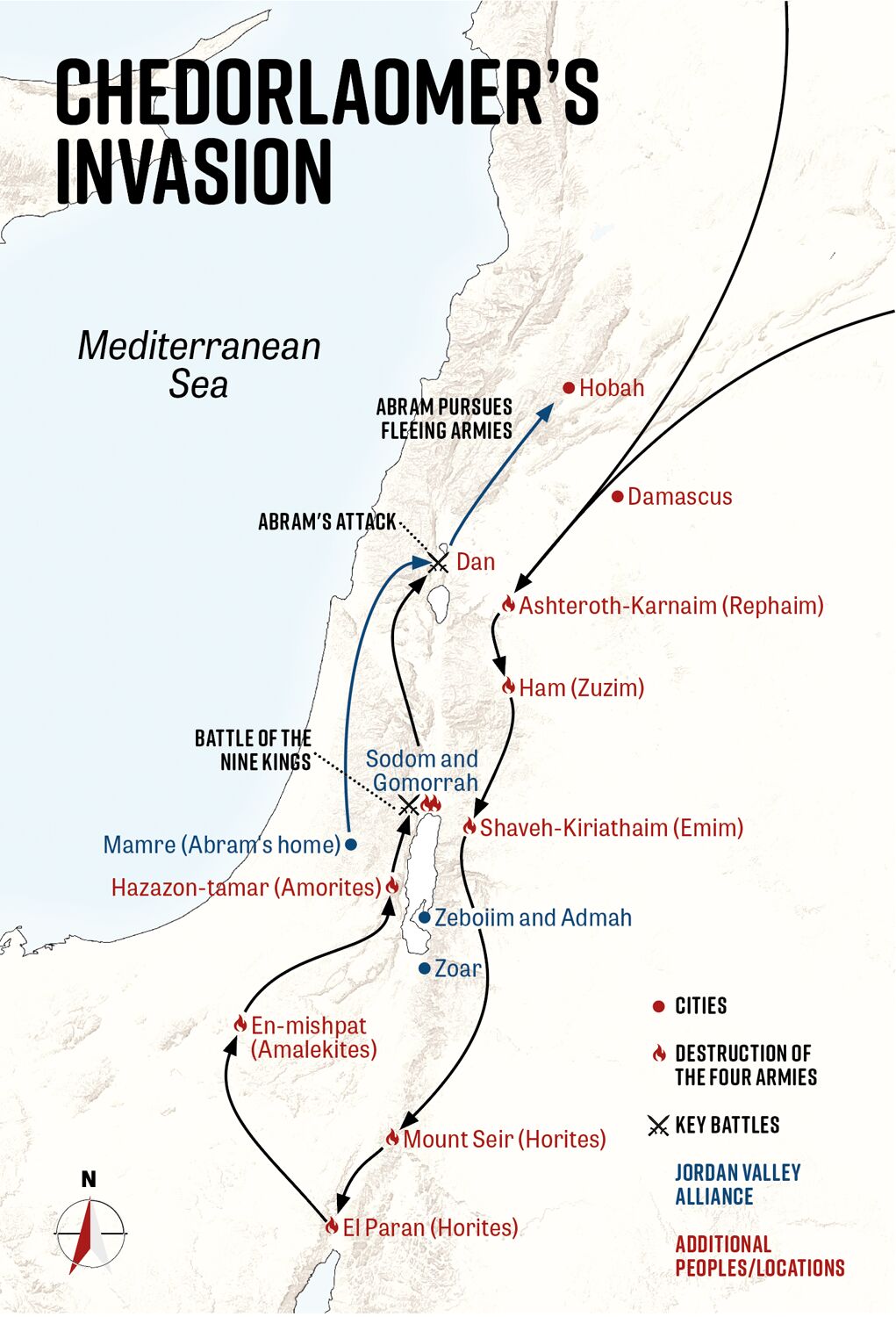

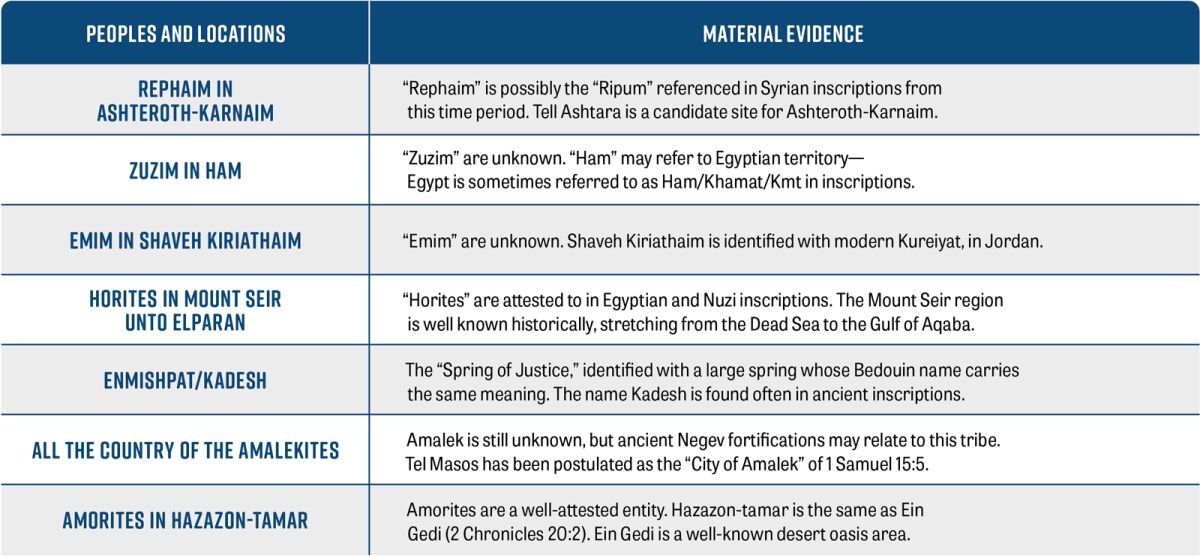

But as Genesis 14 reveals, these five Jordan Valley city-states were not the only ones to bear the brunt of invasion. Genesis 14:5-7 record that, as the four kings invaded the Levant, various tribes were assaulted en masse, including the Rephaim, Zuzim, Emim, Horites, Amalekites and western Amorites. Verse 7 indicates that King Chedorlaomer and his allies zig-zagged through the Levant, effecting maximum destruction. Various peoples were attacked in specific cities. Others were slaughtered throughout their entire country (such as the Horites and the Amalekites).

Finally, the Jordan Valley kings emerged in what must have seemed a futile defense. The battle was staged in the “vale of Siddim—the same is the Salt Sea” (verse 3). Unsurprisingly, the five valley kings were defeated, with the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah fleeing and bogging down in “slime pits” that filled the valley. Others fled to the mountains. The victorious Chedorlaomer pillaged Sodom and Gomorrah and departed with an abundance of goods and captives (verses 10-11).

Abraham to the Rescue

Abram’s nephew Lot was among King Chedorlaomer’s captives (Genesis 14:12). When Abram heard news of Lot’s capture, he immediately leapt into action. “And there came one that had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew—now he dwelt by the terebinths of Mamre the Amorite …. And when Abram heard that his brother was taken captive, he led forth his trained men, born in his house, three hundred and eighteen, and pursued as far as Dan” (verses 13-14; “Dan” here is an anachronistic term, added later by one of the Bible’s early editors; it refers to the furthest northern point of ancient Israel, the location to which the tribe of Dan later migrated).

Moving swiftly with his small force, Abram soon caught up with the massive foreign armies. At Dan, Abram divided his men into smaller squads and, under cover of darkness, attacked Chedorlaomer’s forces using guerrilla warfare tactics. “And [Abram] divided himself against them by night, he and his servants, and smote them, and pursued them unto Hobah, which is on the left hand of Damascus” (verse 15).

At this point, King Chedorlaomer’s armies were just about to exit the Levant. Tidal’s army would have been about to make the shorter journey north into Anatolia, while the three remaining armies would turn eastward toward Mesopotamia to return their territories. But their effort to return home as victors never materialized. Verse 17 records the total defeat of King Chedorlaomer and his allies.

According to Genesis 14, the captives were freed, together with the ransacked goods. A triumphant Abram returned home where he was greeted by the representatives of many grateful peoples, including the king of Sodom and, most notably, “Melchizedek king of Salem … priest of God the Most High” (verse 18).

But Is There a Historical Setting?

How well do the biblical events fit with the known, wider geopolitical picture?

The events described in Genesis 14 fit squarely within what is recognized as the “Elamite Conquest” period. According to conventional chronology, around 2000 b.c.e. Elam sacked Ur and effectively ended the dominance of the Sumerian empire. Elam was catapulted to new, powerful heights.

In The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia, historian Trevor Bryce writes: “Elam [now] became one of the largest and most powerful of the western Asian kingdoms with extensive diplomatic, commercial and military interests both in Mesopotamia and Syria. Its territories extended north to the Caspian Sea, south to the Persian Gulf, eastwards to the desert regions of Kavir and Lut, and westwards into Mesopotamia.”

Elam began its superpower status first with the Shimashki dynasty, followed by a rich Sukkalmah period. Remarkably, this eastern kingdom of Elam’s diplomatic, commercial and military interests extended as far west as Syria—the territory of the Levant! Historian Joshua Mark writes: “Even though details of Elamite culture are vague during this period, it is clear that trade was firmly established and lucrative. Excavations at Susa [Elam’s capital] have unearthed artifacts from India and various points in Mesopotamia and the Levant.” Could some of these artifacts have come as tribute from the vassal Jordan Valley kings?

Prof. Kenneth Kitchen writes, “[I]t is only in this particular period (2000–1700) that the eastern realm of Elam intervened extensively in the politics of Mesopotamia—with its armies—and sent its envoys far west into Syria to Qatna. Never again did Elam follow such wide-reaching policies. So, in terms of geopolitics, the eastern alliance in Genesis 14 must be treated seriously as an archaic memory preserved in the existing book of Genesis …” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament).

And what about the man at the center of it all, King Chedorlaomer, Kudur-La-gomer? It is notable that kings of Elam with the “Kudur-” prefix specifically reigned during this final, grand Sukkalmah period.

At the same time, the other three kingdoms mentioned in Genesis 14 were also present. Moreover, historians recognize this was a period where geopolitical alliances were common. According to Professor Kitchen, this early second-millennium b.c.e. period was “the one and only period during which extensive power alliances were common in Mesopotamia and with its neighbors.”

The Elamite subjugation of Ur resulted in more than just the establishment of Elam as the regional superpower. It also allowed the development of the “Isin-Larsa” kingdom. This small kingdom began in the city of Isin, but later was overthrown and established in the city of Larsa—again, matching with the later Elamite Sukkalmah period. The Larsa state only existed for 150 years, primarily during the 19th century b.c.e. Moreover, the final ruler of the Larsa kingdom was Rim-Sin i, Eri-Aku—or “Arioch of Ellasar.”

What about Tidal? Again, this name is an ideal match for the Hittite name Tudhalia. But history shows that Tudhalia i reigned around 1400 b.c.e.—nearly 500 years after the events recorded in Genesis 14. Actually, historians recognize that “Tudhaliya i” was not the first official with this title. There is a mysterious “proto-Tudhalia” recognized from the most fragmentary of records. In fact, so mysterious is this figure that he is only known in name; historians still debate his official standing. He is speculated as being on the scene between the 19th and 17th centuries b.c.e. This Tudhalia, then, would be a good fit with the original “Tidal, king of nations.”

Collapse of Empires

History books and the archaeological record show that sometime during the 19th to 18th centuries b.c.e., the geopolitical picture in the Middle East underwent a sudden and radical change. The Elamites were overthrown. Larsa was conquered, and a fleeing Rim-Sin was captured. And the region of Anatolia was marred by internal strife. Historian Paul Kriwaczek writes of a “shock of an unprecedented social environment,” with “confrontation … [v]endettas and blood feuds.”

What happened? As is revealed by ancient inscriptions (such as the 18th-century b.c.e. Mari Letters), these powerful kingdoms were sacked by an emerging Amorite power—one that would take over the region and become what is known as the “Amorite First Dynasty.”

I purposely left the biblical “Amraphel, king of Shinar” until last, because this king has been linked in name to the famous ancient ruler Hammurabi. There are a few ways “Hammurabi” can be transliterated, such as Amurapi, which later took on a “divine” form, Amurapi-ili—a close match to the Hebrew “Amrapil.”

Hammurabi was a regional Amorite king of the Sumerian-Shinar city of Babylon. He started out as a relatively minor regional ruler and even referred to one of the kings of Elam as “father.” He is known for his alliances with the then-powerful Elam and Larsa. But sometime during the latter part of his reign, his fortunes dramatically changed. History records that Hammurabi overthrew Elam and Larsa and united Mesopotamia under a newly dominant Amorite power administered from Babylon.

What caused this dramatic power shift in favor of Hammurabi and the Amorites? Historians generally cite a tangle of alliances with Elam and Larsa, and a deceptive and failed power grab by Elam. This alone would fit well with the biblical picture. But going further, could the rise of the Mesopotamian Amorites have anything to do with Abram’s victory against Elam in Syria—a victory for the western Amorites, within whose country Abram lived, and whose people Chedorlaomer attacked? (Genesis 14:7, 13). Could the biblical account of the defeat and humiliation of Elam have tipped the dominoes toward a complete collapse of the primary Mesopotamian power, eventually to be replaced entirely by an Amorite power?

It’s possible that Hammurabi’s emergence as Mesopotamia’s dominant force was a function of Abram’s victory over King Chedorlaomer and his allies.

There is still some dispute about the dating of Hammurabi; many historians place him around 1792 to 1750 b.c.e. (about a century too late to be a counterpart of biblical Abram). However, dating the early Mesopotamian kingdoms is notoriously difficult, and the chronological record remains contested among historians, varying up to centuries (with Hammurabi placed anywhere from the 19th century to the 17th century b.c.e.). It remains entirely possible that Hammurabi and Abram—who at the time of the battle was in his 70s or 80s (Genesis 12:4)—were counterparts.

What is certain is the eventual utter collapse of Elam and Larsa and the ensuing primacy of the Amorites. The geopolitical scene, then, fits well with the biblical account.

So where does the evidence leave us? Details remain unknown. Crucially, though, there is no evidence against the Genesis 14 “battle of nations”—only a burgeoning body of evidence for it. (It goes without saying that many find Abram’s “resistance” unbelievable—but note the sidebar at the end of this article, “319 vs. Four Armies?”.)

To revisit the quotes from the introduction:

“[L]ittle or no historical memory of pre-Israelite events or circumstances in Genesis”? Hardly—rather, the geopolitical situation is a close fit, to the nearest century.

That Genesis 14 is made up of “names and places, none of which can be verified by outside biblical sources”? As we’ve seen, that’s an outright falsehood—and from a “Bible scholar” no less.

Don’t be intimidated by scholarship. Sometimes the conclusions of the “educated” critics may feel like the armies of empires bearing down. But they are no match for a strong faith among even the smallest of armies—like that led by the “father of the faithful,” the patriarch Abraham.

Sidebar: The Rise and Fall of Sodom

The location of Sodom has long been debated, but new archaeological evidence points to Tall el-Hammam, which sits on the northeastern edge of the Dead Sea. This was no small city: During this Middle Bronze Age period, Tall el-Hammam was a fortress of 344 dunams (85 acres), consisting of an upper and lower city, with an additional 970-dunam (240-acre) occupational area outside the city walls.

Many have heard the story of the fire-and-brimstone destruction of Sodom by God. But many may not realize that evidence of this event exists.

Around the early 18th century b.c.e., this site (as well as several others surrounding) came to an almost inexplicable, cataclysmic end. Burned foundations were found of mud brick structures that suddenly disappeared. Skeletons lay mangled. Clay pottery fragments were discovered to have melted into glass. Zircon crystals in the pottery, upon analysis, were shown to have formed within one second—the result of superheating to temperatures perhaps as hot as the surface of the sun. A “tidal wave” of boiling hot salt swept over the land. Mineral grains had rained down, carried by scorching, high-force winds. Ash and debris, about a meter thick in some places, were left behind within the wider 500-square-kilometer (193-square-mile) area of destruction—a scene of utter carnage of biblical proportions. The estimated regional population of 40,000 to 65,000 people would have been killed instantly by this strange event.

What caused the catastrophe? Scientists don’t know. One theory is that an exploding meteor may have been the cause—an “airburst” event that would have required at least a 10-megaton yield to inflict the type of damage witnessed (over 650 times the blast yield of the Hiroshima atomic bomb). Whatever happened, the region was left uncultivable and inhospitable for the next 500 years.

“Then the Lord caused to rain upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven; and He overthrew those cities, and all the Plain, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and that which grew upon the ground” (Genesis 19:24-25). Read our article “Sodom and Gomorrah Proved!” for more information.

Sidebar: 319 vs. Four Armies?

Genesis 14 says that Abram’s army was comprised of only 319 men (including himself). Abram at this time was around 80 years old. Is it really possible that he could defeat four powerful armies?

Clearly, God gave Abram this victory. But the matter of divine intervention aside, history shows that winning such a lopsided battle is possible. Recall the famous Battle of Thermopylae (484 b.c.e.), where 300 Spartans defended the narrow pass from anywhere between 100,000 and 2.6 million Persian troops. (The Spartans were supported by 6,000 backup troops—but these played a more minor role.)

There are numerous examples of severely lopsided, yet victorious battles. In the Battle of Lacolle Mills in 1814, 80 British soldiers held back 4,000 American troops. In the Battle of Blood River in South Africa in 1838, 464 Boers were attacked by 15,000 Zulus. The defense was successful, with only three Boers wounded—compared to 3,000 dead Zulus.

In the Capture of Belgrade during World War ii (1941), only seven German soldiers captured the entire city, which was defended by thousands of troops. In the Battle of Longewala in 1971, 150 Indian troops successfully defeated an advancing Pakistani force of 4,000 soldiers and 40 tanks. Only two Indians were killed.

Was Abram’s rout, with only 319 men, impossible? Historical precedent resoundingly says no.

Tactically, Abram and his small, nimble force had advantages. The large size of the enemy’s armies (at least tens of thousands of soldiers) would have constituted an unwieldy force. Logistically, it would have been difficult to navigate the unfamiliar terrain. Further, Josephus, the first-century historian, records that King Chedorlaomer’s men were drunk and glutted on the spoils. Abram’s men were familiar with the territory and operated under darkness. (They may also have taken advantage of a separation of Tidal’s troops northward to Turkey.)

All that would be required of Abram was to cause chaos and the targeted killing of the military leadership. Further, the king of Sodom was still alive—he may have been able to capitalize on the chaos and join Abram with any of his remaining men in fighting free.

There is room for endless speculation. Whatever the answer, the Genesis 14 account is not only entirely reasonable, it is supported by archaeological and historical evidence.