The Gezer Calendar

Discovered by an Irish archaeologist working for a British company on an excavation in territory controlled by Turkey, the Gezer calendar provides fabulous insight into life in ancient Israel.

R.A.S. Macalister uncovered the calendar in 1908 during an excavation in the city of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem. This ancient inscription, 11.1 centimeters high and 7.3 centimeters wide—about the size of a mobile phone—dates to the 10th century b.c.e. (early Iron Age ii), which is around the time of King Solomon.

Archaeologists get excited about inscriptions because they often provide an eyewitness account of daily life in an ancient culture or civilization. That’s why the discovery of one of the oldest Hebrew inscriptions ever found sparked many archaeologists’ interest; it shines light on the developed language and well-structured life of ancient Israel.

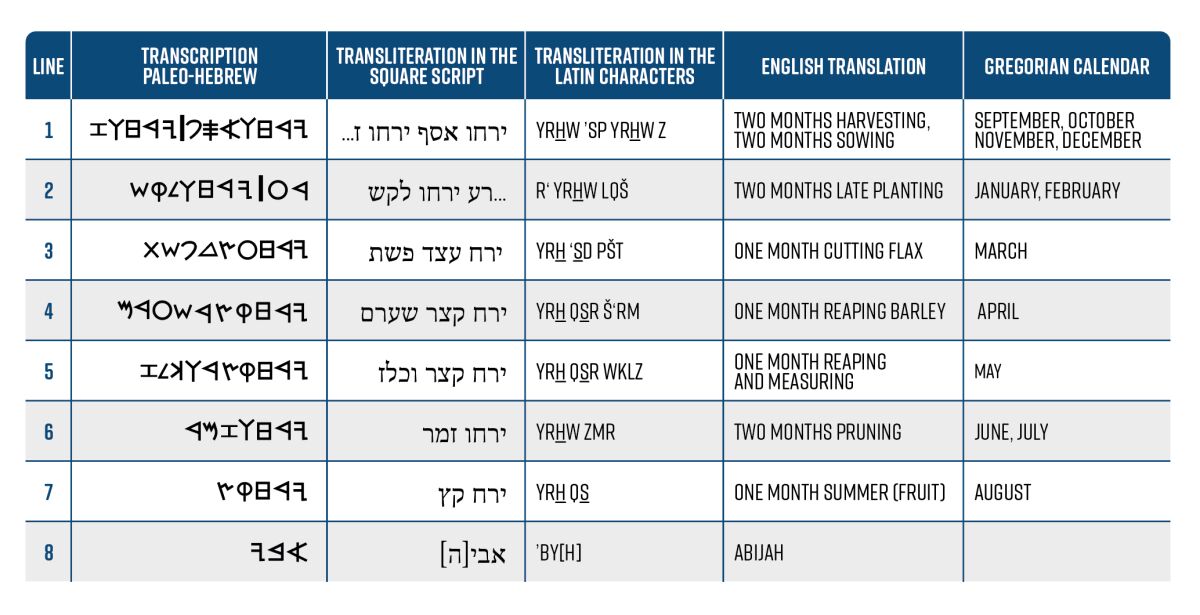

The inscription on the Gezer calendar reads:

Two months harvesting [September, October]

Two months sowing [November, December]

Two months late planting [January, February]

One month cutting flax [March]

One month reaping barley [April]

One month reaping and measuring [May]

Two months pruning [June, July]

One month summer (fruit) [August]

Abijah [name of the scribe]

Importantly, the calendar begins at “the time of harvesting.” It was most likely written around this time too. This would have been around the time of Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles—a festival of great rejoicing and gladness following the ingathering of the large fall harvest. The Israelites looked forward to this time of year, including its agricultural abundance and annual fall holy days.

The fall harvest marked the end of one agricultural year and the beginning of the next. The fact that the calendar begins with the “two months gathering” makes sense, because the Bible reveals that the agricultural, land sabbath and Jubilee years were anchored to this seventh month—Tishri (Exodus 23:16, 34:22, Leviticus 25, Deuteronomy 15). From the two months of gathering beginning with Tishri, the calendar continues through all 12 months.

Made of soft limestone, the Gezer tablet could easily be written on and then scraped for reuse, making it ideal for a youth learning to write, or perhaps a scribe in training. How this document was used specifically, though, has been a topic of debate. One theory is that the wide, almost sloppy script suggests it was written by a young person practicing his or her Hebrew. Some speculate that it might also be lyrics to an ancient Israelite nursery rhyme, a tune to help young children learn the harvesting schedule. Others suggest it was an official document possibly used to help with taxes paid by farmers.

Despite the varying theories about its author, experts recognize that the calendar was an educational device and proves the Israelites were literate. This is especially insightful since few very Hebrew inscriptions have been discovered.

Some scholars argue that the inscription is not actually in Hebrew, but rather is a form of Phoenician writing. However, the evidence for this is weak, and many scientists have made a strong case that the text is paleo-Hebrew. In the 10th century b.c.e., after Egypt’s pharaoh destroyed the Canaanites in Gezer, he gifted the city to his daughter, King Solomon’s wife (1 Kings 9:16). Gezer became an Israelite city shortly before this calendar was created. This explains why Hebrew writing was found in a city that was previously Canaanite.

The Bible records that after receiving Gezer from the pharaoh, Solomon expanded it into a grand, well-fortified city. Excavations at Gezer have exposed some of the same architectural features, including the six-chambered gates, that have been found at Hazor and Megiddo (and possibly Jerusalem). These gates, described in 1 Kings 9:15, indicate that a strong, unified government was present to standardize their construction across Israel. They also help prove that King Solomon was a powerful and wealthy monarch, and not the small-time hilltop chieftain some claim.

Finally, one of the most interesting features on the Gezer calendar is the signature at the bottom: the name Abijah. The Bible makes several references to individuals named Abijah, virtually all of which are from the 10th century b.c.e. The name “Abijah” is mentioned 20 times in the Bible; of these, 16 refer to three leading individuals who lived in the 10th century: Jeroboam’s son Abijah, Rehoboam’s son and successor King Abijah, and David’s “chief man” Abijah.

Names commonly fall in and out of popular use throughout history. While the specific biblical figure of Abijah cannot be proved archaeologically by the Gezer calendar, the common use of the name during this time frame does corroborate the biblical account.

Want to see the Gezer calendar in person? You’ll have to book a flight to Istanbul, Turkey. When this artifact was discovered in 1908, Israel was still under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Today the Gezer calendar is on display in the Museum of the Ancient Orient. Whether you see it in person or through photographs, this artifact supports the biblical account of Gezer being a major Israelite city in the 10th century b.c.e. with established agricultural systems, well-fortified walls and a highly developed language.