The Serpentine Symbol of Healing: A Biblical Origin?

We live in a world full of symbols. Symbols of all shapes and sizes and colors embellish everything from flags to machines to food packaging. There’s a good chance that right now you are surrounded by dozens of symbols, each with its own special meaning and origin.

During the coronavirus pandemic, one symbol has been especially prominent. It is everywhere, plastered on everything from mundane cleaning equipment to ambulances to medical schools and journals to health-care companies. It is part of the official logo of the World Health Organization (who). This is the snake wrapped around a pole, a symbol universally associated with health and medicine.

Where did this popular symbol come from?

Rod of Asclepius

The symbol of the snake-entwined staff is known as the “Rod of Asclepius.” It traces back to Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, who is mentioned by Homer in the Iliad (circa eighth century b.c.e.). Statues of Asclepius appear as early as the fourth century b.c.e., where depictions generally show him holding a rod with a snake coiled around it.

Exactly why a snake-wrapped rod is connected to the Greek god of healing is unclear. Among the various theories, one relates to the fact that snakes shed their skin, thus symbolizing regeneration, “healing.”

But there is evidence of a deeper meaning, an even earlier source for the Greek symbol.

Numerous ancient Greek stories either parallel or are directly derived from earlier biblical sources. Study ancient Greek literature and mythology and you will see parallels in their stories of a Creation, a Great Flood, and a “Tower of Babel.” You’ll see stories remarkably similar to biblical accounts from Noah’s ark to Moses’ “ark of bulrushes.” The colorful personalities and tales attached to some of the greatest figures of Greek mythology are remarkably similar to Bible personalities: Gaia and Eve, Cronus and Cain, Hephaestus/Vulcan and Tuvalcain (as pronounced in Hebrew), Apollo and Jubal, Deucalion and Noah, Hercules and Samson.

What about Asclepius and his snake-rod? Could this also have a biblical connection?

‘Make You a Fiery Serpent’

The book of Numbers describes the Israelites’ sojourn in the wilderness, after they were miraculously delivered from slavery in Egypt. What began as a journey of jubilation quickly turned into one of discontent and murmuring. By chapter 21, as they were skirting around the Land of Edom, the Israelites had become impatient with the long route toward the Promised Land.

The people began to blaspheme God. They condemned Moses and complained that he had brought them out of Egypt only to starve them in the wilderness. They detested the manna God miraculously supplied from heaven (verse 7).

Notice how God responded: “And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died” (verse 8).

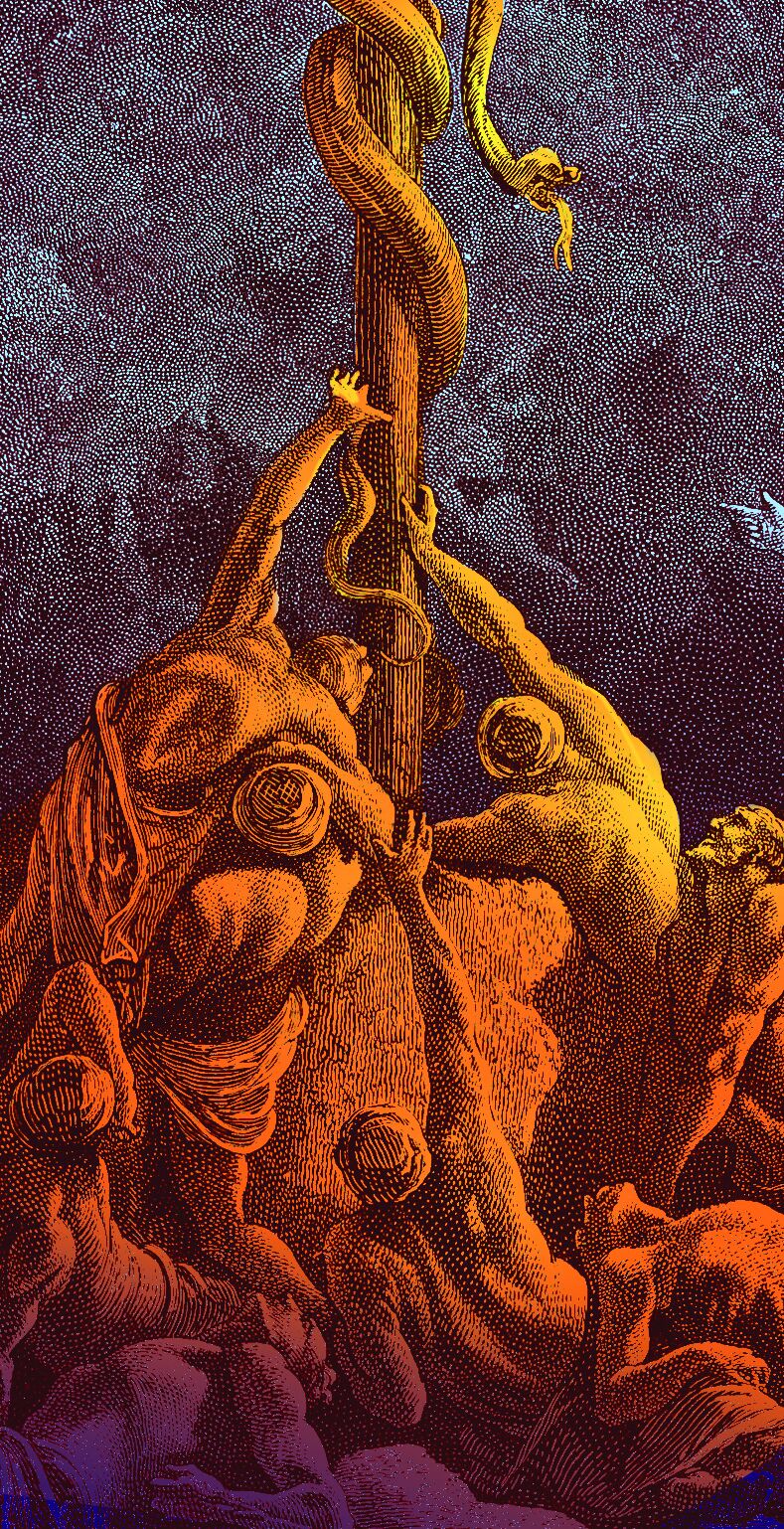

With thousands of poisonous snakes slithering about, the Israelites quickly changed their attitude. They begged God to release them from the curse. Moses prayed on their behalf, and God gave him a peculiar set of instructions. “And the Lord said unto Moses: ‘Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole; and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he seeth it, shall live.’ And Moses made a serpent of brass, and set it upon the pole; and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he looked unto the serpent of brass, he lived (verses 8-9).

Interesting! God had Moses erect a pole wrapped with a metal snake. This must have been a sizable object, since the whole encampment of Israelites was able to see it. It must have taken some time to forge as well, during which time many Israelites continued to lose their lives. (It is unclear whether the symbol was constructed of brass or of bronze—the original Hebrew word is difficult to translate.) To be healed, the Israelites simply had to look at this gigantic symbol.

‘Merely a Brazen Thing’

This isn’t the only biblical reference to this serpentine symbol.

The statue Moses fashioned was carried all the way into the Promised Land. Perhaps it was kept as a reminder of God’s miraculous healing and as a warning for disobedience. Clearly it was an enduring and well-known symbol in the nation. But by the time of Hezekiah about 700 years later, it had become a pagan idol and was being worshiped.

“Now it came to pass … that Hezekiah the son of Ahaz king of Judah began to reign … And he did that which was right in the sight of the Lord, according to all that David his father did. He removed the high places, and brake the images, and cut down the groves, and brake in pieces the brasen serpent that Moses had made; for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it: and he called it Nehushtan” (2 Kings 18:1-4). Hezekiah had the statue destroyed, naming it “Nehushtan,” essentially meaning “merely a brazen thing.” The Hebrew words for brass (“nehoshet”), snake (“nahash”), and divination (“nahash”) share the same root, thus indicating some word-play for this item.

Was this serpent-entwined pole the inspiration for the Greek symbol? This story is often cited in some form when discussing the origin of Asclepius’s rod. The parallels are obvious: a serpent on a rod, specifically relating to healing—and one that became the subject of pagan worship. Surely this is more than coincidence.

But how did it get to Greece? There are a couple of possibilities.

Merchants of Dan

The Bible shows that this symbol survived in Israel for 700 years, and was even worshiped by the Israelites. So it was common, well-known, and held in high esteem. Foreigners visiting Israel would have certainly seen this idol. The Philistines, Israel’s closest neighbors, would likely have been familiar with it. And the ancient Philistines had close ties to the Greek world.

In addition, the tribe of Dan also had close connections with the Greek world. Excavations at Dan’s “capital,” Tel Dan, have revealed a number of Greek artifacts dating to the Israelite period of rule. Dan was known as a brutal, seafaring people. This tribe actually matches quite closely with a seafaring people called Danaoi/Danaan, described by Homer as fighting alongside the Greeks. The Danaoi joined the Battle of Troy on their ships—an event placed around the same time as a biblical battle in which the tribe of Dan was condemned for having disappeared in their ships (Judges 5:17).

Further, Dan is known as being the most pagan of all Israelite tribes, not only worshiping idols but stealing them as well (Judges 18). One of Dan’s symbols was a snake (Genesis 49:17; according to Jewish tradition, this was the symbol on the tribe’s flag). And the tribe was known too for its migrations.

Herbert W. Armstrong explained the prophesied “serpentine” nature of Dan in his book The United States and Britain in Prophecy. “In Genesis 49:17, Jacob, foretelling what should befall each of the tribes, says: ‘Dan shall be a serpent by the way ….’ Another translation of the original Hebrew is: ‘Dan shall be a serpent’s trail.’ It is a significant fact that the tribe of Dan, one of the 10 tribes, named every place they went after their father Dan.”

Mr. Armstrong traced the “serpent’s trail” migration of Dan up through the Holy Land (Joshua 19:47; Judges 18:11-12), across the Mediterranean (the Danaan), around the shores of western Europe and up into Ireland with the arrival of the Tuatha de Danann (“Tribe of Danann”). This tribe is described in Irish history as having originally been bitter rivals of the Philistines—just as the biblical tribe of Dan was. “They were principally seamen, and it is recorded Dan abode in ships,” continued Mr. Armstrong. “[N]otice how these Danites left their ‘serpent’s trail’ by the way—set up waymarks by which they may be traced today.”

The same could be said for tracing the origin of the serpentine symbol of healing itself. It is possible that this seafaring, merchant tribe, which we know had contact with the Greek world, passed on tales of such a symbol—or even established its worship in ancient Greece.

Evidence All Around Us

The serpent-entwined rod of healing is a fascinating symbol spanning both ancient and modern times, first emerging in second-millennium b.c.e. Israelite history. (Perhaps there is an even earlier link to Moses. Recall the accounts in Exodus 4 and 7, where God told Moses to toss a rod on the ground, where it became a serpent.) The serpent-rod symbol later reappears in the first millennium b.c.e. in the account of Hezekiah. And it later emerges in Greek texts and artwork.

Of itself, the serpent-rod is not stand-alone proof of the veracity of the Bible, but it does add to the burden of evidence testifying to the events recorded in the Bible.

Very often, stories like the serpent-rod do not originate in a vacuum: They point to a core event that really happened. We see this with events such as creation, the “great Flood” and the “tower of Babel,” among others, all of which are recorded in detail in the Bible. Various cultures and religions all over the world have parallel accounts of these events. Often, as with the serpent-rod, the symbol or story traces back to a source event—one originally recorded in the Bible.

Today many people see the Bible as outdated, a story of fiction with no relevance to enlightened society. The truth is, even in this modern world where the Bible is forgotten, we are surrounded by the Bible! Most people are unaware of it, but so much of what we do—the language we use, the symbols that adorn our flags and emblems, even the way we think—is directly or indirectly connected to the Bible.

In the case of the snake-rod, who would have thought that such a ubiquitous symbol could have such a web of historical connections that go all the way back to Exodus and the Israelites’ journey in the wilderness?