Veracity of Jeremiah Proved in the Lachish Letters

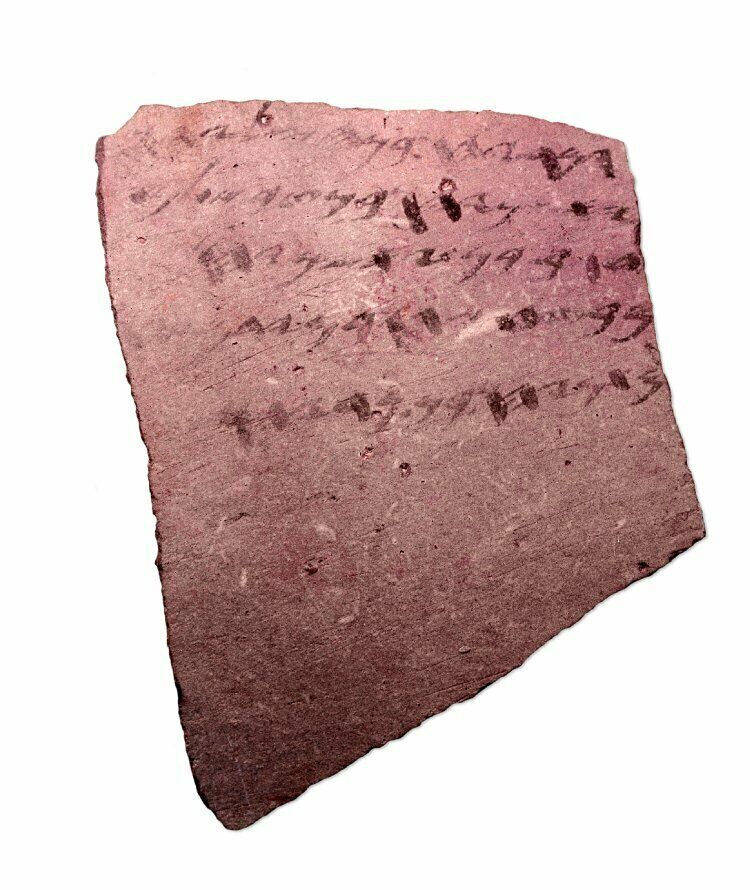

Hebrew ink inscriptions on 18 ostraca (inscribed pottery fragments), dating to around 587 b.c.e., provide a unique glimpse into the closing moments of the kingdom of Judah just before the final Babylonian invasion.

In 1935, 18 ostraca were discovered by the Wellcome Archaeological Research Expedition to the Near East at Tel Lachish. At least 12 of these belong to the same pottery vessel.

The inscriptions, written in an iron-carbon ink by either a reed or wood pen, are the first personal documents in pre-exilic Phoenician-Hebrew script found in the region. The text is very similar to both the Ophel ostracon and the Samarian ostracon. It is written with beautiful cursive penmanship and, although only half of the ostraca are legible, their near-hundred lines provide historical and archaeological backing of the biblical account.

The text uses a dot to serve as a word divider. Interestingly, the dot is frequently omitted, possibly due to the writer’s haste, further evidencing the coming Babylonian invasion.

The 18 ostraca were found in a destruction layer of ash and charcoal in a small room under a gate tower of Lachish’s main defenses.

The letters were sent by Hosha’yahu, the commander of a small outpost north of Lachish, to Ya’osh (Joash), the military governor of Lachish. It appears that Hosha’yahu also acted as a liaison between Ya’osh and the authorities in Jerusalem.

One of these potsherds, Lachish ostracon #3, written in 609 b.c.e., shows that both the Prophet Jeremiah and Uriah warned the Jews to surrender. The ostracon reads, “The commander of the army, Coniah, son of Elnatan, has gone down to go to Egypt …. And as for the letter of Tobiah, the servant of the king, which came to Shallum, son of Yada from the prophet, saying ‘Beware!’—your servant has sent it to my lord.”

Notice how well this text parallels Jeremiah’s account (Jeremiah 26:20-23):

Uriah the son of Shemaiah of Kiriath-jearim; and he prophesied against this city and against this land according to all the words of Jeremiah; and when Jehoiakim the king, with all his mighty men, and all the princes, heard his words, the king sought to put him to death; but when Uriah heard it, he was afraid, and fled, and went into Egypt; and Jehoiakim the king sent men into Egypt, Elnathan the son of Achbor, and certain men with him, into Egypt; and they fetched forth Uriah out of Egypt.

Lachish ostracon #4 says, “May Yahweh cause my lord to hear reports of good news this very day …. Then it will be known that we are watching the (fire) signals of Lachish according to the code which my lord gave us for we cannot see Azekah.”

This stand-alone sherd, separate from the other five that are legible, indicates Hosha’yahu was anxiously waiting to see fire signals from Lachish because he couldn’t see any signal from Azekah, meaning the city had probably already been captured by the Babylonians.

The Judean city of Azekah is mentioned in Jeremiah 34, which gives the history of King Nebuchadnezzar’s invasion. “Then Jeremiah the prophet spoke all these words unto Zedekiah king of Judah in Jerusalem, when the king of Babylon’s army fought against Jerusalem, and against all the cities of Judah that were left, against Lachish and against Azekah; for these alone remained of the cities of Judah as fortified cities” (verses 6-7).

This scripture says that both Lachish and Azekah, high hilltop cities used as communication relays, were captured by the Babylonians. The Lachish Letters provide a brief snapshot of time that fits right in the middle of this passage, after the capture of Azekah and before the Babylonians marched 20 kilometers to besiege Lachish.

According to The Lachish Letters, by Joseph Reider, the letters were examined by a military court at the gatehouse in Lachish after Hosha’yahu lost control of his military fortress to the Babylonians. “Presumably he was accused by his enemies that he delivered his fortress into the hands of the Babylonians without any attempt at defense. … However while the trial was going on, the fortress of Lachish must have fallen too, and with it the courtroom, whose contents were consumed by fire.”

Another potsherd, Lachish ostracon #9, dated to 589 b.c.e., mentions yet another biblical figure in the book of Jeremiah: “May Yahweh cause my lord to hear reports of peace and of good news. And now, give 10 loaves of bread and two measures of wine. Bring back to your servant a word by the hand of Shelemiah concerning what we must do tomorrow.”

Jeremiah 38:1 mentions “Gedaliah the son of Pashhur, and Jucal the son of Shelemiah”. Shelemiah, another name from Jeremiah’s account, is corroborated on this Lachish ostracon.

Renowned archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar discovered two clay bullae referencing these two government officials mentioned in the same verse only a few meters apart. The bullae of Gedaliah and Jucal, or Yehuchal, are currently on display in the Israeli Museum in Jerusalem. (For more information about these two bullae, please visit our online exhibit page “Seals of Jeremiah’s Captors Discovered!”)

Lastly, Lachish ostracon #16, dated to 587 b.c.e., says, “your servant sent it … the letter of sons of [?] … [?]ah, the prophet.” Only the last Hebrew letter of the prophet’s name survived. This could be referring to Jeremiah, Uriah or Hananiah. We cannot be sure which one, but considering his high status and role in Judah, this probably refers to Jeremiah.

Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land by editor in chief Benjamin Mazar and editorial director Joseph Aviram described the Lachish Letters as “the most important epigraphic collection from the time of the First Temple period.”