Digging Up Hebrew

An Israeli friend and musical colleague of mine made international headlines this summer.

Acclaimed cellist Amit Peled was kicked out of a café in Austria. What grievous offense warranted the owner’s refusal to serve him and the two other musicians in his party? They were speaking Hebrew.

“Welcome to Europe 2025,” Peled was quoted by the Times of Israel as saying (July 27).

This resonated with me, having just been in Austria two months earlier—and even having carried on a rudimentary Hebrew conversation with an Israeli family at a tourist site near Salzburg (no one around us seemed to mind).

The current global political climate is ripe with animosity not just toward the Jewish nation and its people but even their language. Of course, the man credited with singlehandedly reviving Hebrew as a spoken language would agree that the language itself was intertwined with the very existence of a Jewish state.

Now 144 years on from when this man first arrived in Jerusalem, his work is maligned by some as not true to the original tongue of his forefathers. After all, as an argument goes, how close could a Yiddish-speaking Russian Jew get to reviving Hebrew as it was once spoken?

A 1952 English book by Robert St. John, now out of print, offers incredible detail on this process and the man called Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. In Tongue of the Prophets, St. John conveyed what he learned from a biography written in Hebrew by Eliezer’s widow.

Ben-Yehuda’s work not only benefited the establishment of “Israel,” it also served as a mighty support to the archaeological work that would come in the years to follow. Biblical archaeology without a nation of Hebrew speakers seems impossible to imagine.

Additionally, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda was himself an archaeologist—of a linguistic sort. The kind of rigorous work he did, the scientific standards to which he adhered, are relatable to anyone leading an excavation. And they make the product of his life’s devotion all the more worthy of the highest esteem.

Miraculous?

Maybe it’s the same for most students of Hebrew, but it wasn’t long into my studies that a tutor provided me with homework about the work of Ben-Yehuda. The worksheet I was given had the Hebrew title “The Miracle of Hebrew” and explained in briefest form the work of Ben-Yehuda.

There is so much depth to what this man did, however, to me it was worth branching out from a two-paragraph, simple-Hebrew account to Robert St. John’s 340-page work.

But can a modern Hebrew speaker really trust that his spoken language is similar to what it was before it went dormant some 2,000 years ago? Setting aside the fact that any language morphs over centuries, is Hebrew’s long hiatus from everyday life an argument against modern Hebrew’s legitimacy?

Ben-Yehuda’s resurrection of Hebrew certainly is “miraculous” in itself—as the word “resurrection” would imply. But scientists and archaeologists don’t like to operate in the realm of “miracles.” They look at what can be perceived with the senses—from what has been verifiably recorded and preserved.

So we will set aside what many would perceive as miraculous. We will set aside what some would insist were the fingerprints of God throughout the process. We will set aside the inexplicable triumph the man achieved—not just over naysayers (from the very people who would actually benefit from his success), but over the terminal illness that was supposed to prevent him from barely reaching adulthood. Instead, we will look squarely at the scientific procedure Ben-Yehuda undertook to present his people with the language they speak today.

Unsurprisingly, the Hebrew Bible appears as a key “artifact” in this whole process. He wasn’t a spiritual or religious man, but he knew Scripture could not be ignored as a central historical source for his mission. Its function was scientific.

Never mind that his naysayers insisted Hebrew was “holy” and only to be used in prayer or religious contexts. Eliezer rejected this. For when Israel’s prophets roamed the streets millenniums ago, did they not use the same language both to relay divine pronouncements and to facilitate commerce in the marketplace? Did not King David use the same language to pen his most heartfelt prayers as well as to govern affairs of state?

The Journey Begins

For those unfamiliar with Ben-Yehuda’s life, here is a brief look at his background, which can scarcely be severed from his passion to resurrect Hebrew.

Born as Eliezer Pearlman in 1858 in modern-day Belarus, he took a different surname and moved in with an uncle to avoid mandatory military service to the czar. This uncle sent him to a nearby rabbinical school where he met an influential rabbi named Joseph Blucker, whose massive library intrigued the young teenager. Blucker drew Eliezer’s attention to one book in particular: a copy of Robinson Crusoe—in Hebrew.

“It was Rabbi Blucker who kindled a spark which grew into a scorching flame that only death would someday extinguish,” St. John wrote. “This spark was a love of the Hebrew language, not only as a vehicle for preserving the words of great Jewish religious leaders and the conveyance of them from generation to generation, but also as a secular language.”

Eliezer’s uncle, however, was horrified by the boy reading a secular book in a holy language, and he kicked his nephew out of his house.

Afraid to go back to his mother, the 14-year-old went to another nearby city and slept in the synagogue which, by custom, remained unlocked through the night. The next morning, a man, surnamed Yonas, found Eliezer and brought him home to his wife, four daughters and two sons.

Eliezer and the Yonas’s oldest, an 18-year-old named Deborah, became fast friends as she taught him French, German and Russian over the next two years. The youngest, an infant named Pola, also grew to have a fascination with the new boy, but more on that later.

Deborah fanned his love for Hebrew. “It is a language of beauty,” she told Eliezer. “It has a melody of its own.”

He eventually went to Paris, where he finished high school and where the idea of a Jewish homeland—a Hebrew nation—became the aim of his life. Eliezer decided to remain there to continue studying medicine, since it was “a profession which could give him a certain social standing … and place him in contact with people in a position to help in the realization of his dream,” St. John wrote.

Around this time, he contracted tuberculosis. The illness that was supposed to be his undoing inspired him to be more productive than he might have ever been. He wrote article after article, with awareness that any of them might stand as his last words.

Working on borrowed time, he wrote to Deborah:

I have the feeling of a person condemned to death, and I so much wish to find a way to utter my last words. For this reason, I work now without sleep to put onto paper the reasons why it is so important for the Jewish world to become inflamed with the idea of returning to the land of our forefathers and working for the freedom to which we are entitled. I have decided that in order to have our own land and political life it is also necessary that we have a language to hold us together. That language is Hebrew [and, as he explained, a modern version for everyday life] …. For all these reasons, I am working like a man with but a few hours to live.

In the following letter, he signed it with a newly chosen surname: Ben-Yehuda (“son of Judah”). He explained this was a Hebrew translation of his father’s Yiddish name. Deborah eventually became his wife.

Archaeologist of Words

The myriad struggles Ben-Yehuda faced in the political and linguistic sphere are too many to detail here. We will look squarely at the process with which he revived Hebrew.

Before he got started in these linguistic efforts, he met an influential friend who told him his effort to modernize Hebrew would be “like building a modern 19th-century structure on a solid foundation thousands of years old.”

Eliezer replied: “One will have to spend years searching through Hebrew literature and in libraries all over the world for words which once were in the language and disappeared.”

His friend astutely observed: “You will have to be detective, scholar, magician and midwife all combined.”

He also had to be somewhat of a persuader. He arrived in Jerusalem in what was then known as southern Ottoman Syria in 1881 (what he preferred calling “Israel”) on what religious Jews would have been observing as Simchat Torah (the eighth day of the Sukkot festival).

His effort included convincing the approximately 24,000 Jews then in the land (speaking a variety of languages) to adopt one. One Yiddish man told Deborah and Eliezer that the couple was speaking a dead language. To which Eliezer replied: “You are wrong, my friend. I am alive. My wife is alive. We speak Hebrew. Therefore, Hebrew is alive.”

Though not religious, they adopted many Jewish customs in order to be taken seriously by their new neighbors.

He began a magazine with a name that was a Hebrew play on words: Hatzvi means deer or gazelle, but the word came explicitly from Daniel 11:16, 41, which used “eretz hatzvi” to describe “the glorious land”—as the word for gazelle could also mean glorious or beautiful.

The magazine itself introduced and popularized recently discovered or “created” Hebrew words to its readership little by little.

He also began teaching Hebrew—in Hebrew—“a method which generations later would be used by one of the most successful language schools in the world,” St. John wrote.

And of course, only Hebrew was spoken among Eliezer, Deborah and their children. (In terms of pronunciation, he preferred the Sephardic over the Ashkenazic, since he believed Sephardic was closer to ancient Hebrew.)

Ten years after their arrival in the Holy Land, Deborah died of the very illness that was supposed to claim Eliezer’s life. About a year later, he married her now 19-year-old sister, Pola, who renamed herself a more Hebrew-sounding “Hemda.”

A motto hanging over his desk read: “The day is short; the work to be done so great!” Eliezer continued to work urgently.

This urgency was partly credited to “Israel” having its own anthem and flag but no single language to bind everyone together. To Eliezer, this meant a Hebrew dictionary needed to be published as soon as possible to establish proper standards for pronunciation and teaching.

Hemda had some catching up to do to keep up with a Hebrew-speaking household. It began in earnest when her new husband sat her down and opened the Bible—pointing at the first word, explaining the Hebrew phrase “in the beginning,” and then the next word, and then the next. “Day after day she took lessons from him,” St. John writes. “He taught her first to read the entire book of Genesis, but each day he gave her a sprinkling of purely household words to learn.”

Meanwhile, he would often pull 17-to-18-hour days working on a Hebrew dictionary. One did not then exist (nor even a Hebrew word for “dictionary”).

His office was littered with paper fragments. But for anyone cleaning his room, no scrap was to be considered trash. It may have contained a word, notes about a word or its etymology. Each might have represented weeks spent in a distant library.

Early in the process, a scrap of a “lost” word became literally lost in the hubbub of daily activity, which caused no end of grief in the Ben-Yehuda household (and later was found in the cuff of Eliezer’s pants). Shortly after this, Eliezer instituted a filing system and hired two theology students to help document his work.

The “science” of this process was clearly seen in how well he researched each word.

He would end up scouring thousands of books over decades—“the works of many forgotten poets and writers of little fame,” St. John wrote. “He had even perused countless private manuscripts. He had had to become master not only of written English, French, German, Russian and Hebrew itself, but also of the ‘sister languages’ of Arabic, Coptic, Assyrian, Aramaic and Ethiopian.”

Part of this included a two-month stint in London—working tirelessly in the British Museum. St. John, aptly leaning on the archaeology analogy, wrote regarding any time he found a “lost” word: “On that occasion, he was as excited as, years later, the archaeologists would be when they suddenly uncovered the ancient wealth of King Tutankhamen.”

A Pure Language

“Ben-Yehuda wanted to keep Hebrew pure,” St. John wrote (emphasis added throughout). “He wanted to help make modern Hebrew a consistent and beautiful language, without harsh sounds; without words which grated on the ear because they were inconsistent with the ancient music of the language. That was the basic theory on which he worked.”

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s task was not just to resurrect dead words, nor even to find words that had nearly disappeared; it was to generate words for the countless number of new items and ideas that had developed in society for the past 2,000 years.

Part of Hebrew’s revival being kept pure meant properly handling the formulation of these new, modern words. Rather than arbitrarily making up words, or leaning on “loan” words (which he called the “bastardization” of the language), he looked to see if there was a root, concept or idea in history that could be used as a resource, a starting point (the word for “bicycle” was a blend of “wheel” and “two”). If not, he would go to the Semitic sister languages (e.g. Arabic) to see what he could “graft” into Hebrew. Because of these languages’ similarity to Hebrew, he did not view this as any “bastardization.”

This included some uphill efforts against people borrowing words themselves. For example, since the French called “fashion” mode, most Hebrew speakers then preferred to say modah, but Eliezer, with Hemda’s help, created ofnah, based on the ancient Hebrew ofen, meaning style or manner.

Some questioned what gave him the authority or power to decide such things. “The answer he always gave,” St. John wrote, “was that he was merely the excavator. He dug out a word and put it on display; if they were pleased with it and felt a need for it, the word was there for them to use. If they rejected it, the word died aborning.” For instance, some words gained usage in his home but never outside, so the word in fact died. The word he preferred in his house for “tomato” was closer to a colloquial Arabic word, but the word commonly in use (agvania—from a root meaning “to love sensuously”) was the one that stuck among the populace.

The Witnesses

Ben-Yehuda’s dictionary was a “Herculean task”—as Prof. Samuel Krauss, a language scholar from Budapest, described it. Krauss highly complimented Eliezer’s scientific methods and said that “no one but a man with tremendous enterprise and boundless energy” could undertake such a feat.

“He said that if Ben-Yehuda’s work had no other results, it had been worthwhile because of the new light it threw on many obscure passages in the Bible,” St. John wrote.

Not only was this to be the first Hebrew dictionary in modern history (and probably ever), it would be more than just a list of words, definitions and standards of pronunciation. It would be a multilingual dictionary (with French, German and English translations). It would include origins, comparisons with sister words in other Semitic languages.

But each word would also include a witness, as Eliezer called it—examples of usage in history, where applicable. “This had given him one of his greatest problems of research; to find in ancient, medieval and modern literature as many different ‘witnesses’ or uses of each word as possible.”

He excavated 335 different ways to use lo (no/not), and 210 “witnesses” for ken (yes).

“Many of his ‘witnesses’ were quotations from the Bible and other religious books,” St. John wrote, “but there were often long passages from secular literature, from the works of little-known poets, or from manuscripts he had found somewhere in a distant library.”

And so some words took up multiple pages—starting with the first one (av: father). The word for “because” (ki) would have 24 columns.

The Bible Speaks

Eventually, Eliezer replaced the motto over his desk to read: “My day is long; my work is blessed.”

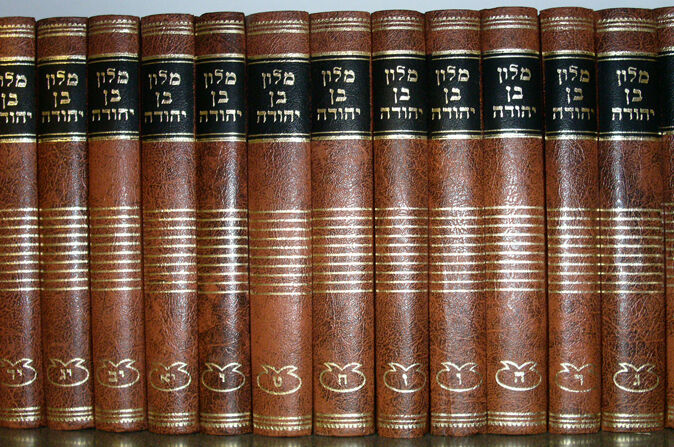

Though Eliezer Ben-Yehuda outlived anyone’s expectations for his lifespan, his 64-year life was not long enough for what became a 17-volume dictionary, each volume averaging 600 pages each. He completed only five of them before his death in 1922, and fittingly the last word he was working on was nefesh—the word for soul. Nevertheless, he left much of the material required for the remaining volumes, which his widow, one of his sons and other devotees helped finish.

His approach was wholly scientific and sound. Truly, as Professor Krauss had suggested, Eliezer’s work would be “worthwhile because of the new light it threw on many obscure passages in the Bible.” At the very least, it opened a unique and broader access to the Hebrew Bible—at least for some of its literary virtues. (For more, read “The Powerful Poetry of the Hebrews.”)

The world into which Eliezer was born was one where his mother “knew the Hebrew words of the Bible, but she had never really understood what the words meant,” St. John wrote. Decades later, the ability to think, speak, hear and dream in the language of the Bible has given millions the ability to see, in an unfiltered way, the beauty of the biblical text itself.