Discovered: Lachish Ostracon Bearing Biblical Name ‘Shaphan’

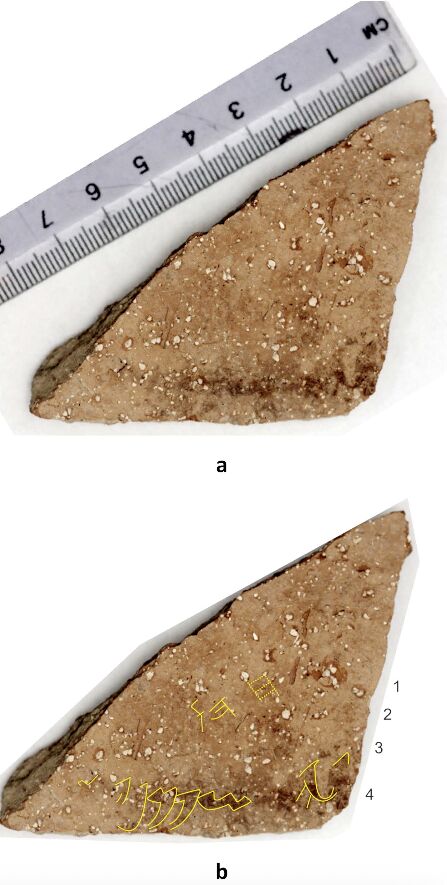

Admittedly, it’s not much to look at: A small, roughly palm-sized triangular sherd of pottery, with an extremely faint line of ink marking along the bottom. It’s an ostracon—an inked potsherd inscription—albeit in extremely poor condition.

Uncovered in 2016 during the Fourth Expedition at Tel Lachish (a joint excavation between Hebrew University and Southern Adventist University, directed by Professors Yosef Garfinkel, Michael Hasel and Martin Klingbeil), analysis of the sherd was only published recently in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, in a paper titled “A New Hebrew Ostracon From Lachish,” by Daniel Vainstub, Hoo-Goo Kang, Barak Sober, Iris Arad and Yosef Garfinkel. The sherd dates to the end of the Iron Age—discovered in a layer destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 b.c.e. (Level ii)—and though it doesn’t tell us much, as far as content goes, it does bear the rare name of a particular biblical figure also on the scene at the same time: Shaphan.

Hyperspectral scanning was used to produce a clearer image of the faded inscription, with the following reading presented (from what appears to have originally constituted a four-line text—most of the lines impossibly faded):

- [ ]ח[ ]

- [ בן] י]הו ]

- [ ]

- [ ] ב10+[?6] שפן בן

- [ ]h[ ]

- [ ya]hu [son (of) ]

- [ ]

- On the 1[6?] (day of the month) Shaphan son (of) [ ]

Shaphan—Who?

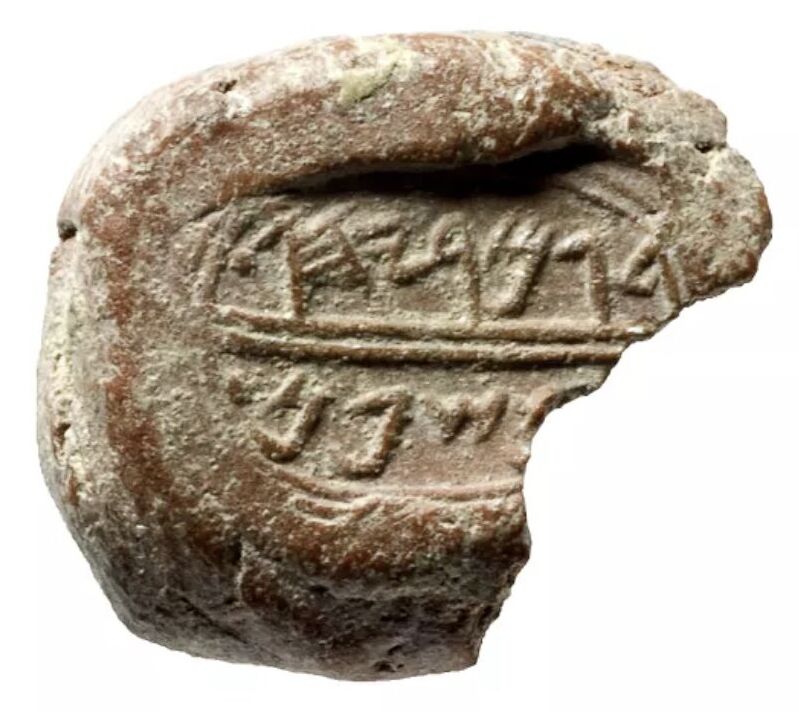

The name Shaphan is an exceptionally rare one—both in the Bible, and in archaeology. Intriguingly, in both cases, it is only found right at the very end of the biblical kingdom period—just prior to the fall of Jerusalem. This artifact represents only the second time the name has been found in an archaeological context—the other, on a bulla (seal stamp) discovered during the late Prof. Yigal Shiloh’s City of David excavations.

The authors wrote: “The only person bearing the name Špn in the Bible is שפן בן-אצליהו בן-משלם, the royal scribe involved in the discovery of the book of the Torah in the Temple of Jerusalem and the subsequent cultic reform in the time of Josiah (2 Kings 22; 2 Chronicles 34).

His descendants continued to hold high office in the kingdom’s government until its destruction. A bulla of his son גמריהו [ב]ן שפן [Gemariah son of Shaphan], who also served as the royal scribe (Jeremiah 36:10-12, 25), was found in the City of David (Shoham 2000: 31). This bulla is the only occurrence of the name in a provenanced epigraphic source predating our ostracon.

Unlike other officials mentioned in the book of Jeremiah, whose bullae have likewise been found—the princes Jehucal, son of Shelemiah, and Gedaliah, son of Pashhur, who were enemies of the prophet (Jeremiah 37:3; 38:1)—Gemariah son of Shaphan was supportive of Jeremiah’s message.

And when Micaiah the son of Gemariah, the son of Shaphan, had heard out of the book all the words of the Lord, he went down into the king’s house, into the scribe’s chamber; and, lo, all the princes sat there, even … Gemariah the son of Shaphan …. Then said the princes unto Baruch: ‘Go, hide thee, thou and Jeremiah, and let no man know where ye are.’ And they went in to the king into the court …. And it came to pass, when Jehudi had read three or four columns, that he [king Jehoiakim] cut it with the penknife, and cast it into the fire that was in the brazier …. Moreover Elnathan and Delaiah and Gemariah had entreated the king not to burn the roll; but he would not hear them (Jeremiah 36:11-12, 19-20, 23, 25).

Perhaps in his respect for the written testimony, Gemariah was not so removed from his father Shaphan, who himself is recorded as having brought the newly discovered book of the law to King Josiah. (Josiah’s reaction to it was quite the opposite to that of his son Jehoiakim—rather than tearing up the scroll, Josiah tore his garments.)

And Hilkiah answered and said to Shaphan the scribe: ‘I have found the book of the Law in the house of the Lord.’ And Hilkiah delivered the book to Shaphan. And Shaphan carried the book to the king …. And Shaphan read therein before the king. And it came to pass, when the king had heard the words of the Law, that he rent his clothes (2 Chronicles 34:15-16, 18-19).

Could the Lachish ostracon, then, refer to one and the same Shaphan? Impossible to know for sure—and in any event, this is a figure already corroborated by the aforementioned bulla. Still, in the case of the ostracon, it does date to the right period, and it appears that the name is an extremely rare one—so it is quite possible that it refers to one and the same official.

But why rare? This is something lost to non-Hebrew speakers, but the name Shaphan refers to that peculiar rodent-like creature known variously as the hyrax, coney or rock badger, found in parts of the Middle East (including Israel) and Africa. In modern Hebrew, the term has also come to be used somewhat interchangeably for rabbits. It is also a colloquial term for a “coward,” or someone shy (given the nature of the associated animal).

Small wonder, then, that the name is not one you’re likely to come across today—neither, apparently, anciently.