Celebrating Ancient Persia!

The October 1971 party thrown by the shah of Iran was breathtaking. It took 10 years to plan and lasted five days. The Guinness Book of World Records recorded it as the most “well-attended” international gathering in history.

For almost a week, more than 600 foreign dignitaries, including 65 heads of state, left behind their sprawling mansions and palaces to travel deep into the Iranian desert to sleep in tents pitched on dunes on the outskirts of Persepolis, capital of the ancient Persian Empire.

But this wasn’t camping the way you and I do it. Guests stayed in spacious, custom-furnished, air-conditioned tents, constructed in traditional Persian style. Hairdressers and make-up artists were jetted in from Paris. Drapes and flowers were imported from Italy. They ate the finest food, catered by Maxim’s de Paris, which closed its Paris location for nearly two weeks to prepare for the banquet. Around 150 chefs, bakers and waiters were imported. The world’s master hotelier, a Frenchman, was brought out of retirement to manage the waitstaff. Attendees dined on fine china and sipped expensive wine from goblets made of Baccarat crystal.

There were fireworks displays, performances from the world’s finest musicians and spectacularly choreographed parades by Iranian soldiers, all dressed in traditional Persian garb. Two hundred fifty custom-built red Mercedes-Benz cars zipped across the desert carrying foreign diplomats. The price tag of the grand affair, according to the Telegraph, was $100 million (almost $800 million today).

Why host such an extravagant party?

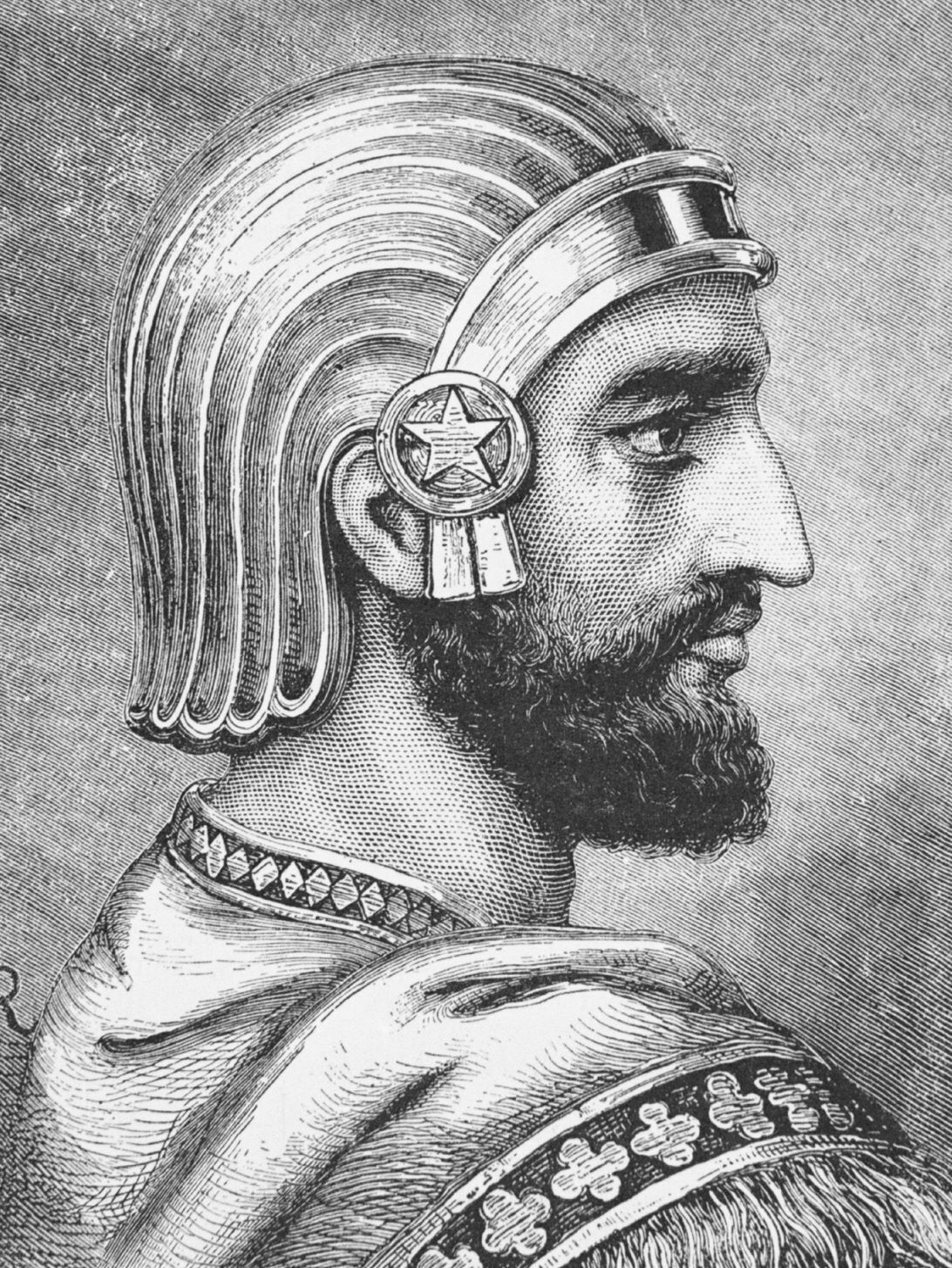

The shah of Iran was celebrating the 2,500-year anniversary of Cyrus the Great and the founding of the Persian Empire.

Remembering Ancient Persia

Before the 1930s, Iran was widely known as Persia. Today the names Iran and Persia remain interchangeable—though each evokes radically different perceptions. The Persians are an Indo-European people whose biblical heritage traces back to Shem, the son of Noah. The Jewish historian Josephus recorded the Persians as being descendants of Shem’s son Elam (Genesis 10:22).

Up until the mid-sixth century b.c.e., the Persians were a small, relatively powerless kingdom situated on the plains of Mesopotamia, north of the Tigris River and east of the Zagros Mountains. For centuries, the Persians, together with the Medes and other smaller kingdoms, lived in the shadow of much more powerful neighbors, primarily the Assyrians and Babylonians.

Persia’s tranquil days spectating from the sidelines ended around 550 b.c.e., when Cyrus succeeded his father as king. King Cyrus, a brilliant soldier and administrator, unlocked Persia as a military and imperial power. In his first campaign, he conquered the more powerful Medes, who in defeat accepted an invitation to join forces. Within two decades, King Cyrus was ruling over a kingdom of unprecedented power and size, one that stretched from Thrace in the west to Egypt in the south to the Indus River in the east.

In 539 b.c.e., Cyrus sacked the greatest city on Earth and the capital of the mighty Babylonians. Babylon at the time was spectacular for its strength and majesty; it boasted one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Herodotus recorded that the city covered 507 square kilometers (196 square miles) and was protected by an outer wall that was 95 meters (311 feet) high and 27 meters (87 feet) thick. Access through the fortified walls was controlled by more than 100 bronze gates. The mighty Euphrates River wended through the city, irrigating its famed hanging gardens.

But Babylon’s impressive walls and “impenetrable” gates weren’t enough to stop Persia’s king. Employing a risky but simple strategy, the Medo-Persian army diverted the waters of the Euphrates, then used the riverbed to penetrate Babylon’s gates. Once inside, Cyrus’s army easily and quickly conquered the city, including its inebriated king (for more, click here).

King Cyrus now ruled the largest, most powerful empire in the world. As administrators, Cyrus and his successors were unique. Persia’s kings were unusually altruistic and enlightened. They respected and tolerated the customs and traditions of the people they ruled over. Starting with Cyrus himself, they had a penchant for humanitarian leadership. “Under the close supervision of his government, [Cyrus] permitted the conquered peoples to retain their own customs and religions and their own forms of government,” explains Stanley Chodorow in The Mainstream of Civilization. Ancient Persia’s humanitarianism is attested to both archaeologically and biblically. This was explored in detail in our July-August issue of Let the Stones Speak.

This is the history the shah of Iran was celebrating at his gigantic 1971 party. He was celebrating his nation’s “pre-Islamic origins,” a time when Iran was sophisticated and enlightened, a truly impressive superpower.

Persia and the Bible

The Hebrew Bible revolves mainly around Israel, the people who inhabited the southern Levant. But while the biblical text concentrates on Israel, it features several foreign peoples and kingdoms. Of all the kingdoms featured in connection with Israel, the Achaemenid Empire of King Cyrus and his successors is perhaps the most prominent.

The Medo-Persian Empire is referenced in Isaiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther. In fact, the Achaemenid dynasty played a significant role in several important biblical events.

The book of Ezra records the return of the Jewish exiles to Jerusalem to rebuild the temple under the decree of Cyrus the Great. Ezra opens by recording the benevolence of Persia’s king. “Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the Lord by the mouth of Jeremiah might be accomplished, the Lord stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia …” (Ezra 1:1). Ezra here is recording the fulfillment of a prophecy in Isaiah 44, where God said He would use Cyrus as a “shepherd” and that he would “fulfill my purpose.” The biblical text not only attests to Persia’s humanitarian tendencies, it explains them.

Not long after the events recorded in Ezra, Nehemiah—a cupbearer in the royal court of King Artaxerxes—was granted permission to return to Jerusalem to rebuild its walls. Then there’s the book of Esther, also set in the Persian Empire during the reign of King Xerxes (biblical Ahasuerus), father of Artaxerxes.

The biblical text also includes prophetic references to Persia. In Isaiah, Cyrus is referred to as the Lord’s anointed (Isaiah 45:1), an unusual designation for a non-Israelite ruler, which signifies his role in God’s plan to restore Israel. Similarly, the book of Daniel, written during the Babylonian and Persian periods, includes visions and prophecies that mention the Persian Empire as part of the broader narrative of world history. In Daniel 6:2-3, King Darius of Persia promotes Daniel, a young Jewish man, to a position of great power within the mighty Persian Empire. During Daniel’s public promotion, the king of Persia issued a decree to “all the peoples, nations, and languages that dwell in all the earth,” demanding “that in all the dominion of my kingdom men tremble and fear before the God of Daniel” (verses 26-27).

In Daniel 2, Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar has a dream in which he sees a powerful image in the shape of a king or warrior. Daniel explains the meaning of the image, which is made from four distinct materials. The head of gold represents the Babylonian Empire, while the chest and arms of silver represent the Medes and Persians.

In Daniel 7, Babylon’s King Belshazzar receives a vision of the same four kingdoms, each now uniquely represented by an animal. In this dream, the Medo-Persian kingdom is symbolized by a bear with three ribs in its mouth. The lumbering bear represents Persia’s territorial might, while the ribs represent Babylon, Lydia and Egypt—the three main regions conquered by Medo-Persia.

In Daniel 8, the young prophet describes a vision in which he sees a “ram standing on the bank of the [Euphrates] river. It had two horns; and both horns were high, but one was higher than the other, and the higher one came up last. I saw the ram charging westward and northward and southward; no beast could stand before him, and there was no one who could rescue from his power; he did as he pleased and magnified himself” (verses 3-4; King James Version). Some biblical scholars recognize this as a depiction of the Medo-Persian Empire, with Persia being the more powerful (“higher”) horn.

The vision continues in verses 5 through 8, which depict a virile male goat rapidly descending (“touched not the ground”) from the west. This fast-moving military force smashes into the ram, breaking both its horns and trampling it to pieces. This goat also has a “notable horn,” a symbol of a powerful leader. According to some Bible scholars, this is a vision of Greece’s sudden and dramatic invasion of Persia under the leadership of Alexander the Great in 333 b.c.e.

Iran’s history is spectacular not only for its geographic enormity, military exploits and administrative and humanitarian enterprises; it’s spectacular and important for the way it converges with the Hebrew Bible, with numerous biblical characters and events.

An Armstrong Connection?

More than 60 years ago, when the shah of Iran was making preparations for his spectacular celebration, he commissioned the construction of 18 candelabra. During the weeklong celebration, these 7-foot brightly lit giants, each weighing 650 pounds and decked with 802 pieces of Baccarat crystal, stood in the midst of the royal tent where all the world leaders gathered to dine. Together, these shimmering beauties—and the history of King Cyrus and ancient Persia that they embodied—dazzled the kings and queens, presidents and prime ministers at the shah’s royal banquet.

Today, two of those candelabra perform their duty in the grand lobby of Armstrong Auditorium in Edmond, Oklahoma. Much like the great king they were created to celebrate, these candelabra light our “Kingdom of David and Solomon Discovered” archaeological exhibit!

They are stunning. But as breathtaking as they are in appearance, it’s the story behind them we most cherish. Our candelabra were part of the celebration of the 2,500-year anniversary of Cyrus the Great and the Persian Empire. The shah intended that these candelabra awaken the Iranian people and the world to Iran’s majestic history—with the Jewish people and the Hebrew Bible!