Archaeology has provided no real evidence of this event—until now. Thanks to the new reanalysis of an enigmatic Ophel pithos inscription by expert epigrapher Dr. Daniel Vainstub, there is some fascinating scientific evidence to support this history.

The Ophel inscription analyzed by Dr. Vainstub, a scholar from Ben Gurion University of the Negev, was first discovered in 2012. The artifact was uncovered by Herbert W. Armstrong College students participating in Dr. Eilat Mazar’s Ophel excavation funded by Daniel Mintz and Meredith Berkman. The clay artifact was found among a number of large, broken pithoi (clay storage vessels) pieces embedded in a void in the bedrock.

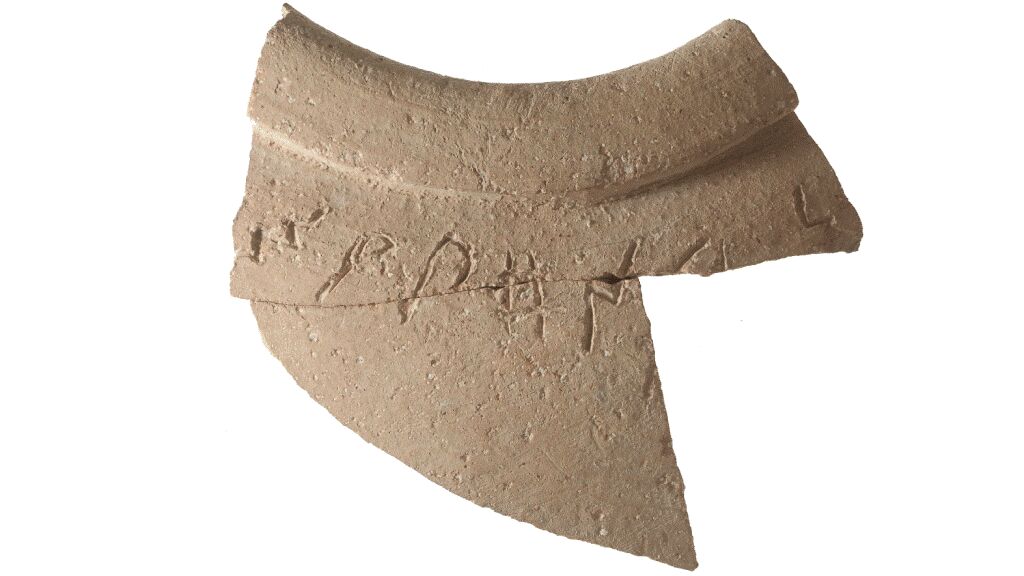

Reviewing the pottery, we were stunned to discover that one of the sherds—part of the rim of one of the vessels—contained a comparatively large inscription. Given that the pottery dated to the 10th century b.c.e.—the time period of Israel’s united monarchy—the discovery was hailed as the earliest alphabetical inscription ever found in Jerusalem and among the earliest found in Israel. (This dating was corroborated last year in a meticulous stratigraphic and ceramic analysis published by Dr. Ariel Winderbaum.)

Exactly what the inscription read though—and even the exact language it was written in—remained elusive. We knew the language was Semitic, but that’s about it. The prevailing view was that it was a Proto-Canaanite inscription. Some claimed it was early Hebrew. Given the fragmentary nature of the inscription, however, there was no consensus about what it said exactly (some theories claimed it was a reference to “wine”).

April brought a major development in the ongoing conversation about the elusive Ophel inscription.

In an article published in Hebrew University’s Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology, Dr. Vainstub presented an entirely different conclusion—that the language of the inscription is actually Ancient South Arabian (asa).

This territory, situated at the far western end of the Arabian Peninsula (in the area of modern-day Yemen) has been widely identified by scholars as the area of the kingdom of Sheba. That’s not all. Dr. Vainstub also explained that the inscription refers specifically to a type of incense, called ladanum (Cistus ladaniferus).

According to the new interpretation, the inscription on the jar reads, “[ ]shy l’dn 5.” The first three letters are a continuation of a previous word. However, “l’dn 5” means “five measures of ladanum.” Dr. Vainstub’s reading of the inscription differs from other readings, most of which suggest the text is Canaanite. According to Vainstub, two of the letters in the inscription pose a problem for the Canaanite theories. These two letters, he says, have much closer parallels in the South Arabian language than they do in the Canaanite.

Even the interpretation of the letter representing a quantity of “five,” in South Arabian form, is a good fit. We know that this type of pithoi had a capacity of roughly 110 to 120 liters. The Judahite ephah, a common measure in the Bible, equates to about 20 to 24 liters. Therefore, the storage vessel would have logically been able to contain precisely this numeric quantity of product—five ephahs.

In an interview with Brent Nagtegaal on our Let the Stones Speak podcast in April, Dr. Vainstub noted that the word ladanum is not found in the Bible. Upon deeper investigation, however, Vainstub concluded that ladanum is described in the Bible using the word šǝḥēlet. He drew this conclusion after studying several sources from the Middle Ages that equate the biblical word šǝḥēlet with ladanum.

The word šǝḥēlet refers to one of the four ingredients required for making the incense used in the tabernacle, and later the first and second temples. This recipe is documented in Exodus 30:23.

Dr. Vainstub also explained that, until recently, our limited understanding of the Ancient South Arabian script has hampered the ability of scholars to interpret inscriptions in this language. Because this field has “expanded enormously in recent decades,” scholars are now able to gain further insights. “The discovery of the Ophel inscription marks a turning point in many fields,” noted Vainstub. “Not only is this the first time an asa inscription dated to the 10th century b.c.e. has been found in such a northern location, but it is also a locally engraved inscription, attesting to the presence of a Sabaean functionary entrusted with incensearomatics in Jerusalem.”

In short, Dr. Vainstub believes the inscription to be a Sabaean trade liaison stationed in Jerusalem, as opposed to visiting.

He concludes that the pithos inscription is evidence of some sort of 10th-century b.c.e. trade highway between southern Arabia and Jerusalem (a distance of over 2,000 kilometers). The biblical account speaks to this in the description of the queen’s visit.

During the 10th century b.c.e. and onward, the kingdom of Sheba “thrived as a result of the cultivation and marketing of perfume and incense plants, with Ma’rib as its capital. They developed advanced irrigation methods for the fields growing the plants used to make perfumes and incense,” according to the article from the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. The perfumes and incense were then exported to the Levant.

Two later biblical prophets, Isaiah and Jeremiah, both drew attention to the spice and incense trade from the land of Sheba.

Dr. Vainstub believes the inscription was engraved by a native speaker of the southern Arabian language who was stationed in Jerusalem and involved in supplying the incense spices. This is because petrographic analysis of the jar shows it to have been made from Jerusalem-area clay. The writing was made before the vessel was fired. This would mean there were Sabaean speakers in Israel at the time of King Solomon who were involved in supplying the incense spices.

The findspot for the inscription—Jerusalem’s Ophel—is also a logical location for the presence of spices and incense. The Bible records that two centuries after King Solomon, King Hezekiah was storing expensive spices in his royal treasure house, which would have been located on the Ophel. In the narrative, King Hezekiah mistakenly showed a visiting entourage from Babylon all the wealth of his kingdom, including the spices.

Most intriguingly, Dr. Vainstub’s new reading is another piece of evidence to add to the sometimes fierce debate over the nature of 10th-century b.c.e. Jerusalem (and by extension, the entire kingdom of Israel). Was Jerusalem at this time the rich, powerful, well-fortified capital that we read about in the biblical text? Or was it a small, unimportant village, as some minimalists claim? The presence of an established trade route between South Arabia and Jerusalem would certainly bolster the former argument!

Finally, the 10th-century dating of the inscription and the archaeological context it was discovered in fit with the biblical chronology of the time period for the Queen of Sheba’s visit to King Solomon’s Jerusalem and its temple (not far, we might add, from the findspot location).

As Vainstub bluntly stated in April, “This inscription doesn’t prove the visit of the Queen of Sheba to Jerusalem; her name is not written on the vessel. But it proves that there was a connection between the kingdom of Solomon and the kingdom of Sheba.”